One hundred years ago, the world was recovering from war and Tampa was in a recession thanks to the end of wartime production. Newly extended voting rights hinted at a changing political landscape. A pandemic had just loosened its grip on people across the globe.

In other words, 1920 looked a whole lot like 2020.

Just as it appears to be again, Tampa was at a turning point. But history provides a more positive outlook on the future. Our population set us up for success; in 1920, Tampa was Florida’s second-most populous city, with 51,000 residents to Miami’s 29,000. Developers responded to the steady growth by adding to the city’s physical footprint, and neighborhoods like Sulphur Springs, Palma Ceia, Davis Islands and Temple Terrace sprung up throughout the decade. West Tampa, which had previously been its own city, was annexed by its neighbor and officially became part of Tampa by 1925.

In 1920, Tampa was also on the cutting edge of communication and entertainment, launching the first licensed radio station in Florida (WDAE, still in operation today) and airing the country’s first complete church service over the airwaves.

In 1926, the Tampa Theatre opened as “the South’s Most Beautiful Theater,” with its intricate Classical and Mediterranean design elements that survive to this day.

The parallels between then and now are readily apparent. Tampa is the state’s third fastest-growing city, behind only Jacksonville and Miami. Physical development is at a fever pitch, with projects like the Westshore Marina District, Midtown Tampa and Water Street Tampa altering the layout and skyline of the city on a near daily basis. Innovation is now centered around the northern part of town, where researchers at the University of South Florida and medical institutions like Moffitt Cancer Center are finding answers to global problems.

To take a visual look at how Tampa has changed in the past 100 years, we scoured the Hillsborough County Public Library’s archive of images from the Burgert Brothers studio to find photos that captured the city as it was in 1920. You’ll then see how that same image would appear today, with details on how the location has evolved over the century.

North Franklin Street

Post World War I, the hub of Tampa’s commercial activity was North Franklin Street. The city’s Federal Exchange Bank opened on the corner of Franklin and Twiggs in the late 1800s, around the same time as the original Maas Brothers store, which welcomed its first shoppers in 1886. After outgrowing its original space on the corner of Franklin and Zack, Maas Brothers purchased the American National Bank Building across the street in 1920 and built a new eight-story store, the one longtime Tampanians might remember from their childhoods.

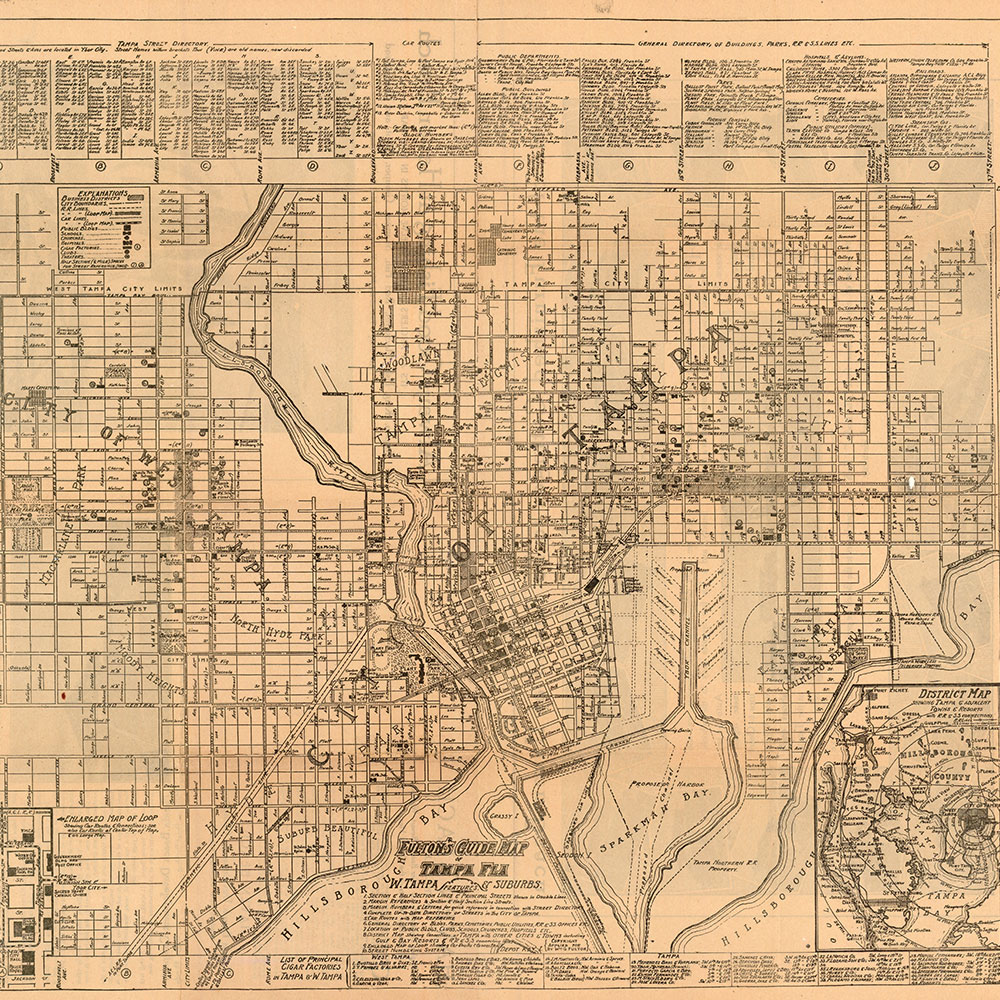

For generations of Tampa residents, downtown department stores like Maas Brothers and the neighboring Woolworth (which opened in 1915) were the destination for everything from daily necessities to Christmas gifts. The Franklin Street corridor was easily reachable from nearly every corner of the city thanks to the streetcar. According to a map created by cartographer Jake Berman last year, nearly every one of the city’s streetcar lines ran along or crossed Franklin Street, giving Tampa residents coming from as far away as West Tampa, Ballast Point and Palmetto Beach access to downtown’s resources.

Today, the North Franklin area is on the rebound. The advent of the suburban shopping mall and the closure of the street’s anchor department stores in the mid-20th century hastened the street’s decline. With the exception of the long-standing Tampa Theatre (which turns 94 this year) and the Hub dive bar, North Franklin Street had few businesses to speak of until the mid-2010s.

Now, it’s beginning to come alive again with restaurants and bars like CW’s Gin Joint, Osteria, Mole Y Abuela, Bavaro’s and Dio Modern Mediterranean. Development has happened even faster on the segment of Franklin Street north of I-275; there, the Hall on Franklin and the Rialto Theatre have helped anchor Tampa Heights’ revitalization in recent years.

The street is once again being looked at as a key artery for Tampa’s public transportation. Last year, HART unveiled preliminary plans for an expansion of the TECO Line Streetcar system, with one proposed line running along Franklin Street to connect Tampa Heights and downtown’s central business district all the way down to the Channel District and Ybor City. While the city’s preferred plans currently call for the lines to run along Florida Avenue and Tampa Street, their proximity to Franklin Street — one block away in either direction — would help foster the district’s continued development.

Bayshore Boulevard

In 1920, most people experienced the city’s most recognizable street via trolley car. The wealthy Mr. and Mrs. Chester Chapin of New York founded Consumers Electric Power and Light in 1892. Consumers then launched a streetcar system that ran from Ballast Point to downtown and competed with the Tampa Street Railway and Power Company system that ran from downtown to Ybor City.

After a rate war that involved the two companies undercutting their fares to gain an advantage over the other, Consumers eventually bought out Tampa Street Railway and Power. By 1899, the business became known as Tampa Electric Company.

Until 1953, all property south of Howard Avenue was owned by Hillsborough County, meaning Bayshore was a county road in 1920. Tampa developers

Alfred Swann and Eugene Holtsinger helped set the tone for Bayshore’s iconic design. After dredging the land from what is now Rome to Swann avenues, they added the Bayshore seawall and lighting along it, similar to what exists now. But it was the county that was ultimately responsible for the street, and it was the county that built a 3-mile long two-lane brick road along Bayshore in 1914.

This image was taken just a year before the Tampa Bay hurricane of 1921, the last major storm to deal a direct blow to the region. It damaged large swaths of Bayshore, resulting in a four-year cleanup.

Now, Bayshore Boulevard is perhaps the most enviable address in the entire city; in 2018, the street’s Stovall-Lee House fetched a record $9.5 million selling price, the most expensive single residential property ever sold in Hillsborough County.

Thousands flock to the waterside sidewalk (which is not the longest continuous sidewalk in the world, as is often rumored — that would be the nearly 14-mile long Rambla in Montevideo, Uruguay) each day to exercise along the signature concrete balustrades above the seawall.

Bayshore as it appears today was largely constructed thanks to a Depression-era Works Progress Administration allotment. Damaged portions of the seawall were repaired, the balustrades were installed, wider pavements were created, and the final segment of the road between Platt Street and Magnolia Avenue was completed. Today, close to 30,000 cars drive along Bayshore each day. Senior photographer Gabriel Burgos captured part of the roadway’s 4.5-mile span from a helicopter back in 2012, the second photo in the gallery above.

Ybor City

As Tampa incorporated and developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ybor City was the destination of choice (and, typically, necessity) for the city’s migrants. It housed many of the city’s 150-plus cigar factories, which employed 10,000 people at their peak. Many of those workers lived near the site of this photo — on the corner of 23rd and Sixth, Ybor’s eastern edge — a block from the bustling Seventh Avenue. The neighborhood’s Spanish, Cuban, Sicilian and Jewish immigrants made up both the street’s business owners and its customer base.

Historians believe the city’s cigar industry had reached its zenith by 1920.

That year also saw the industry’s third general strike — called over factory owners’ right to keep an open shop. The strike was not as effective as previous efforts. Manufacturers began hiring women to fill the striking workers’ place, cigar presses began to replace workers entirely, and unions ran out of money to support striking workers. This strike also began pushing skilled workers to find jobs outside of Tampa, spurring the industry’s decline over the following decades.

Today, Ybor City is at the heart of what makes Tampa unique. It’s the center of the city’s history and culture, from the few hand-rollers that still remain on Seventh to the Cuban sandwiches that derive from the mixtos eaten by Tampa’s first cigar factory workers. Ybor is still a bastion for culinary development, like the new farmer-focused restaurant Barterhouse or the neighborhood’s blossoming craft beer scene (anchored by Coppertail Brewing, Zydeco Brew Werks, BarrieHaus Beer, Rock Brothers and Tampa Bay Brewing).

After its near-destruction in the mid-20th century thanks to urban renewal policies, Ybor City has been slow to recover. But signs point to progress with major projects on the horizon, like the Hotel Haya, which is completed and awaiting the rescheduling of its grand opening. On the history front, the long-awaited Tampa Baseball Museum is expected to open next spring in the former Al Lopez house on Ninth Avenue.

Plant Park

French architect Anton Fiehe designed the grounds of the then-Tampa Bay Hotel to be a taste of the tropics in the middle of Central Florida. In 1913, Life magazine described the park as 42 acres of “luxuriant tropical shrubbery and flowers, beautiful palm fringed walks, fountains and shady nooks, facing the Hillsborough River.” Fiehe handpicked the Sabal palms that lined the park’s riverfront walkway, and the area’s benches were specifically designed to mirror the ones found in New York’s Central Park. In addition to rare or new plant species like orchids, bananas and bamboo, the park was also home to a menagerie of bears, peacocks, monkeys and other wild creatures; some were later moved to ZooTampa when it opened in 1957.

But by 1920, a decade before the hotel closed, Plant Park was primarily the site of parties, games on the expansive lawn, concerts and picnics for both Tampa’s well-heeled residents and the working class.

Now, the park is quite a bit smaller at just under 7 acres, but it has been designated a local historical landmark. It’s also home to public art and Anton Fiehe’s original Sabal palms. The existing park benches are replicas of Fiehe’s 19th-century version. Each one of the 25 is dedicated to friends of the park like Ronald L. Vaughn (the University of Tampa’s president). Others memorialize famous individuals who played an important role in the hotel’s history. One remembers Theodore Roosevelt, who used the hotel as a headquarters during his time as a colonel in the Spanish-American War. Another recalls Babe Ruth, whose longest home run ever happened at Tampa’s Plant Field and landed at what is now the university’s Sykes College of Business.