If they build it, will Tampa Bay come? After a decade of fickle fan support and inconsistent ticket sales, the Rays are looking to set up home base where Tampa’s rich baseball history first took root: Ybor City. The historic neighborhood just so happens to be Exit 1 off I-4 — a serendipitous coincidence for a team that’s looking to start fresh. Grab your peanuts, Cracker Jack and Cubans as we take you inside the “who, what and why” behind this major-league decision, and get a preview of what comes next as the Rays try to make their next-generation field of dreams a reality.

***

On February 9, the Tampa Bay Rays identified Ybor City as the preferred site for their new stadium, ending months of rumors and speculation while also raising a few questions (and eyebrows).

That afternoon, TAMPA Magazine posted a note of congratulations to the team on our Instagram account. Comments were split almost exactly down the middle, with positive reactions ranging from clapping emojis to baseball puns. For every comment that called the announcement a good move, an-other remark a few lines below deemed it a bad one. The skeptics’ thoughts (including one comment that said just “#traffic”) essentially boiled down to one idea: How are we going to pay for this?

More specifically, who is going to pay for this?

The Tampa Bays Rays 2020 — a nonprofit group named for their “clear vision” to rally support for a Rays move to Tampa — believes it has the answer.

The group, which includes the heavy hitters pictured at right, formally announced its existence and purpose at the February announcement. Over the next few months, the organization will be amassing support for the stadium effort from both community members — through a petition on their website — and business leaders.

“This is not the kind of thing that the Rays are going to accomplish on their own,” Ron Christaldi says. “This has to be a community effort first and foremost, and it’s got to be led by the fanbase of the Rays and the business community. Without that support, this won’t happen.”

Like many of the other 2020 members, Ken Hagan, who has been involved with the stadium search since 2010, says building a new ballpark in Ybor City is more about the team remaining in Tampa Bay than the team leaving St. Petersburg.

“From the very beginning, we stressed the importance of keeping the team in the region,” Hagan says. “At this point, the options are the team moving to Tampa or leaving the area altogether.”

“We see ourselves as Tampa Bay’s team,” Rays principal owner Stu Sternberg says. “The Rays are part of the identity and fabric of the community.”

The significant task of ensuring the Rays remain Tampa Bay’s team, while now rapidly picking up pace, was first taken on more than a decade ago. It nearly ended before it truly began.

Meet the players behind the Tampa Bay Rays 2020

Stepping Up to the Plate

The Rays’ search for a new ballpark site in St. Petersburg began shortly after Stu Sternberg bought the team in October 2005. Within a few years, after a 2008 World Series appearance made little long-term impact on the team’s low attendance, it became clear that Tropicana Field wasn’t working as a major league stadium.

“People throughout baseball were surprised by the lack of attendance and corporate support,” Sternberg says. “Clearly there was an issue.”

In 2010, Sternberg, Ken Hagan and Chuck Sykes joined then-St. Petersburg Mayor Rick Baker and other Pinellas County business leaders to form the ABC Coalition, studying where, why and how the Rays should play in the Tampa Bay region. Though two of the five spots the coalition identified as feasible stadium locations included Tampa’s downtown and Westshore areas, the city of St. Petersburg and then-Mayor Bill Foster did not allow ABC to formally present its findings to Hillsborough County or consider any Tampa sites.

That changed in 2014, when St. Petersburg Mayor Rick Kriseman reached an agreement with the Rays allowing them to look outside of the city and Pinellas County; the city council made it official a year later by amending the team’s use agreement. Both Sternberg and Tampa Mayor Bob Buckhorn lauded Kriseman’s apparent willingness to acknowledge a regional benefit to the Rays’ potential move across the bridge.

“Mayor Kriseman had to have the political courage to do that,” Buckhorn says. “Both of us have recognized that [the site selection] is up to the Rays, and we have to rally behind them.”

Buckhorn, along with Hagan and Sykes, was part of the steering committee that would negotiate with the Rays once they were given the green light to look for sites in Hillsborough County. After beginning with what Hagan estimates to be 12 to 15 sites in February 2016, the team’s guiding principles for the search led them to an intriguing option: Ybor City.

“We evaluated each site against our selection criteria, and it became clear that we had a really great opportunity in Ybor City,” says Melanie Lenz, the Rays’ senior vice president of strategy and development.

One initial hurdle to the Ybor site was land ownership, Hagan says. Multiple people owned pieces of the site’s 14 acres when it was first identified as a possible stadium location, but in 2016, BluePearl Veterinary Services CEO Darryl Shaw bought all the parcels as part of a multi-year, $63 million purchase of land throughout Ybor City. Having all the parcels in the hands of just one individual made it easier for the group representing the Rays — led by Ron Christaldi and Chuck Sykes — to work toward an option agreement for the land.

“That was a big step,” Hagan says. “Then the team really began consulting on what the new stadium could be. That gave us a strong indication this was the preferred site.”

According to Hagan, the Rays internally identified Ybor as their choice in early 2017, with site control coming in the fall, followed by the official announcement in February of this year.

“I was pretty ready to name Ybor City the site of choice,” Sternberg says. “My team felt that it was the heart and soul of Tampa Bay. There’s a unique history of baseball in the region, and we’re hoping to bring a space that’s a home for baseball for years to come.”

Tampa & Baseball

Baseball has a long and illustrious history across Tampa Bay. While Tampa hosted the area’s first spring training in 1913 at the Tampa Bay Hotel’s Plant Field, the city of St. Petersburg hosted at least one spring training team for 94 consecutive years, from 1914 to 2008. On this side of the bay, Tampa has produced hometown heroes like four-time World Series champion Tino Martinez, who grew up working in West Tampa’s Villazon & Co. cigar factory. But baseball is singularly a part of Ybor City’s story — making it an obvious choice for a major league ballpark, says Mayor Buckhorn.

“Our roots emerge from Ybor City,” he adds. “Immigrants built a foundation upon which we stand, and having baseball is a part of that history. If you look at who Tampa has sent to the major leagues, it’s the kids of the Ybor immigrants, the longshoremen’s children who played in Belmont Heights.”

Tampa’s Cuban immigrants formed their first organized baseball team in 1887, almost 20 years before the founding of Major League Baseball. The city got its first minor league team, the Tampa Smokers, in 1919 and signed their most famous player in 1926. Al Lopez, an Ybor City native and son of Spanish immigrants, played professional ball briefly in Tampa before working his way up to the major league Brooklyn Dodgers in 1928. He became Tampa’s first representative in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977, and his childhood home now houses the Tampa Baseball Museum.

“A Rays stadium in Ybor would create a new chapter in Tampa’s base-ball history and bring a baseball culture that began 130 years ago full circle,” says Chantal Hevia, the president and CEO of the Ybor City Mu-seum Society and the Tampa Baseball Museum. “It would open up an opportunity to create a living history of Tampa’s baseball heritage that can be honored and celebrated now and by future generations.”

Jason Woody, president and CEO of the Lions Eye Institute — an eye bank and ocular research center headquartered in Ybor City — and a fourth-generation Tampa native sees a potential Rays ballpark as an homage to neighborhood founders like the Lopez family.

“Imagine if we could tell the immigrants who came to Ybor City for a better life that we’d have a baseball field here,” he says. “One of the things they probably missed from their home country was baseball. Now we’re almost giving it back.”

All Roads Lead to Ybor

In their search for a stadium site, the Rays held a series of workshops with groups around Tampa Bay to gather ideas for what a next-generation ballpark could be. According to the Rays’ Melanie Lenz, one question, “What is authentically Tampa Bay?” elicited two consistent responses across the region.

“The number-one answer was our weather and water, and the number-two answer was Ybor City,” she says. “It’s this really special place that already has a great baseball history, diversity and inclusion, unique architecture and more.”

Beyond historic significance, one of the most important pieces of a new stadium is what has arguably caused the most issues at Tropicana Field: location. Chuck Sykes, one of the leaders of Tampa Bay Rays 2020, says he initially supported relocating the ballpark to Al Lang Field in Downtown St. Petersburg before officially joining the site search.

“When I got involved with the ABC Coalition, I realized that it is very important that the ballpark is located in the most central point that we can get it, and in an urban core, ideally,” Sykes says. “The challenge for our region is that the center point is really right over the water between Hillsborough and Pinellas counties.”

“Tampa Bay does not really have an urban core yet, but the only one we’re going to have, in the truest sense of an urban core, is going to be in Tampa,” he adds. “I firmly believe Ybor is, geographically, the best place to put it.”

For more on the geographic advantages of an Ybor stadium for fans, see below. Most importantly, says the team behind Tampa Bay Rays 2020, a centralized Ybor City ballpark would draw in the ones that have always gotten away: businesses.

By the Numbers

By the Numbers

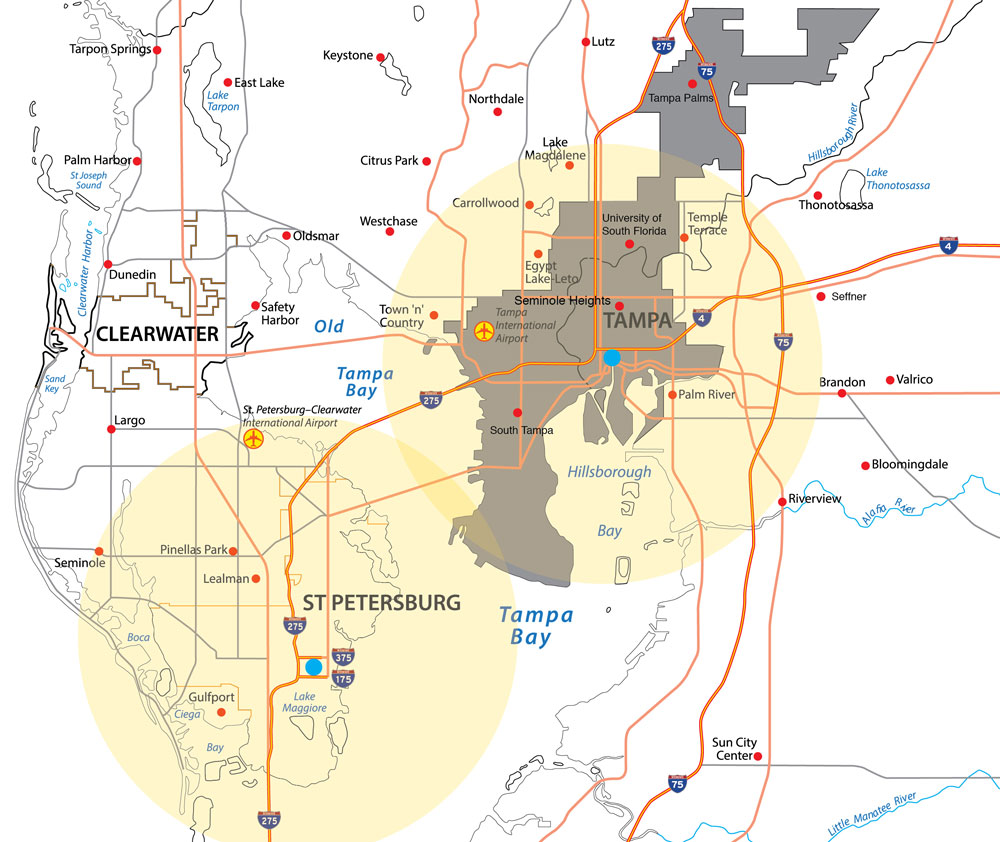

More people live within 10 miles of the Ybor City ballpark site than live within the same distance of Tropicana Field. Pictured above is a 10-mile radius around both locations. In Tampa, that reaches densely populated areas including South Tampa, Carrollwood and Brandon. A large portion of the St. Petersburg radius covers the tourist-heavy beach communities and the bay. According to studies done by research and marketing firm HCP & Associates, 50,000 people live within 2 miles of downtown and Ybor City, while nearly 855,000 live or work within 15 miles of the Ybor stadium site. Additionally, (almost) all roads lead to Ybor City. The stadium site is boxed in by I-275, I-75, the Selmon Crosstown Expressway and I-4, four of Tampa Bay’s largest, most-traveled roadways, making the location convenient for a large part of the region’s population. For example, a family traveling from Downtown Clearwater would only have to drive about three to five additional miles to get to a Rays game in Ybor City instead of Tropicana Field.

Back to Business

According to just about everyone involved in the Rays’ stadium search, the team has a ticket problem.

“If you look at the other 29 teams in the MLB, with almost every one except for the Rays, two-thirds of their tickets are held by companies and one-third are held by the general public,” Chuck Sykes says. “We’ve had the ratio reversed forever. When you’ve got someone at work saying, ‘Hey, do you want four tickets for the game?’ and you’re not paying for them, it’s just easier to get tickets used. You just get a better attendance flow when more tickets are held by companies.”

In addition to ticket sales, Sykes’ Rays 2020 partner, Ron Christaldi, says financial commitments, like sponsorships and naming rights, are crucial to the stadium effort.

“What Chuck and I are laser-focused on now is taking pledges in this community for that support,” he says. “Without that support, the Rays wouldn’t be able to contribute toward the stadium effort in a way that would make it viable. Businesses have this opportunity to help ensure we make this ballpark a reality.”

Those pledge-makers will be members of the Rays 100, a select group of local business leaders willing to make a substantial contribution to the cost of a new ballpark. Christaldi calls this the next big step in the stadium-building effort, which is slated to launch shortly after TAMPA Magazine’s print deadline. He says response from the business community has been largely positive so far.

“Our problem has not been finding 100 people but narrowing it down,” he says. “We’ve had about 270 so far who were interested in supporting the effort, and we’re going to find a way to include everyone.”

According to both Christaldi and Sykes, more demonstrated corporate support will make it easier for the Rays to contribute a larger piece of the overall stadium cost. For now, owner Stu Sternberg just says the team is looking for as much support from the business community as possible.

“We have great partners and sponsors, many long-term, so we’re just looking for more,” he says.

As many business leaders are still considering making financial commitments to the team, Ken Jones, president and CEO of Third Lake Capital — an investment firm that owns Centro Ybor and is a partner of Ashley Furniture — is drumming up support for the Rays in his own company and other Ybor-based businesses.

“Part of what we’ve discussed is encouraging people to get excited, encouraging colleagues to buy season tickets and go to games,” he says. “We’re telling the story of why a stadium makes sense for Ybor City.”

While declining to give specifics, TechData CEO Bob Dutkowsky says his company plans to continue supporting the Rays.

“We are committed to the Tampa Bay community and, by extension, the assets that make this an amazing place to live and work — one of which is the Rays,” he says. “For that reason, we’ve been dedicated to the Rays’ success here for many years.”

Brand New Ball-Game: What’s Yet to Come

While the Rays and members of Tampa Bay Rays 2020 have been working behind the scenes for years to capitalize on an opportunity like the one that exists in Ybor City, a new ballpark is still not a certain prospect.

“It will be complicated,” Mayor Buckhorn says. “But the Rays deserve our best efforts. We’re going to have to hold hands with everybody, but we have to be willing to walk away from this if it doesn’t work. It has to make sense, as much as we want the Rays here.”

County commissioner Ken Hagan is confident that an Ybor stadium would be Tampa Bay’s last shot to keep the Rays in the region.

“When you have an economic engine [like the Rays], it’s incumbent on political and business leaders to keep that engine here,” he says. “It would give us a major black eye if we lost an MLB team. It could seriously hamper corporate relocation efforts, and it wouldn’t put the community in a great light.”

Still, both Buckhorn and Hagan added that the success of Tampa Bay Rays 2020 and the Rays 100 and the ultimate construction of a new ballpark could, and likely would, lead to a plethora of new development around the stadium, Ybor City, and the entire urban core.

“The stadium will be a catalyst for development, and the ancillary development will help fund the construction of the ballpark,” Hagan says.

While no official investment into the area around the stadium site has been confirmed, Lions Eye Institute CEO Jason Woody says a new ballpark would complement the development already happening in Ybor City.

“Apartments are sprouting up daily, mixed-use buildings are going up, and infrastructure is already being built,” he says. “Places like Bernini and the Columbia are already anchors. Here we’ll have something for everybody, and there will be so much activity going on pre- and post-game.”

A stadium in closer proximity to more homes and workplaces would give fans more time and ability to patronize local businesses, Third Lake Capital’s Ken Jones adds.

“It’s an incredible opportunity to create exponential growth around this area and increase foot traffic and business,” he says. “The movement to Ybor City encourages job creation, economic development and more commitment in the community. There’s a huge ripple effect of the dollar on the community.”

Outside of corporate support, one of the biggest economic impacts to the team and region would come through increased ticket sales to fans willing to make more frequent, shorter trips to the ballpark. One of those fans, Todd Barrow, president of Barrow & Powers Financial Services, is already willing to make his ticket commitment.

“Driving from my home in Lakeland to Tropicana Field takes about 90 minutes, so I attend about 10 games a year,” he says. “That will easily double if they move to Ybor City. I’ll be able to get to the stadium in 35 minutes.”

While the team is thrilled with the idea of fans attending dozens of games a season, owner Stu Sternberg says they hope the newfound proximity to a larger population would encourage more people to go to a few games each year.

“The way I see it, it’s about a family or group of buddies or two people on a date going to one or two games a year,” he says. “Then maybe they’ll go to three or four. That’s how we’ll become wildly successful.”

Beyond pure dollar-for-dollar economics, the Rays have also considered how an Ybor stadium would fit into the surrounding community. For one, says Ron Christaldi, it would be the final piece of Tampa’s ur-ban core, currently anchored by the Tampa Riverwalk, Strategic Prop-erty Partners’ impending Water Street Tampa development, and Ybor City’s entertainment district around Seventh Avenue.

“There’s one gap in that chain of connectivity around downtown, and it’s the stadium area,” he says. “This particular site completes the entertainment district that is Downtown Tampa. It will become not just a destination for baseball but a destination for the community to gather and for people to be entertained.”

The Rays’ Melanie Lenz says the ballpark itself will fit into the overall look and feel of Ybor City, including its scale and architecture.

“It will be contextual and connect with the neighborhood on the north end,” she says. “There is a very strong street grid in Ybor City, so we’re considering how we could bring that in.”

To appeal to both traditional fans and visitors looking for a unique stadium experience, the team is considering out-of-the-box ideas they gathered in workshops with community groups.

“Baseball is a conversational sport with no time limits, so that opens up opportunities to create fan experiences,” Lenz adds. “It could be breaking up the linear seating model and looking at ways to create districts or fan zones. Maybe the first three innings you could take a tour of an on-site brewery with a master brewer. It’s about the experiential economy rather than just the viewing experience.”

Lenz also says, to truly be a neighborhood asset, the stadium will be developed for year-round, non-baseball use, something Tampa Bay Sports Commission executive director Rob Higgins says could help bring more national events to Tampa.

“While there is naturally a lot of excitement around the positive impact of a new ballpark related to Rays baseball, we’re also really intrigued by the potential non-Rays baseball events that a new facility such as this could bring to our community,” Higgins says. “Sports tourism has continued to be a huge economic driver for our community, and first-class facilities have played as big of a role as anything in attracting major events to our hometown.”

It’s events like the Super Bowl and NHL All-Star Game, coupled with major projects like the Ybor City ballpark, that will lead Tampa Bay to become a “tier-one” region, says Third Lake Capital’s Ken Jones.

“Having a new ballpark in Ybor City would validate Tampa Bay as a tier-one region, like Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago,” he says. “You don’t make this kind of investment into a sports enterprise on this level unless you’re a tier-one region. To get the confidence of the MLB, city and county to build the stadium says volumes about the level of region Tampa Bay is.”

When speaking of the Tampa Bay region, leaders like Ken Hagan and team owner Stu Sternberg are sure to include St. Petersburg, a city Sternberg says has been “a great partnership” for the Rays.

“I would have loved nothing more than to have had it work at Tropicana Field,” he says. “The goal was not to build a new ballpark. We think we have a great facility now, and I would have been absolutely comfort-able staying in St. Pete. But now we have seen that site is not as accessible as it should be.”

On the other side of the bay, Chuck Sykes sees Tampa’s opportunity to create a cutting-edge ballpark in the urban core as a once-in-a-life-time chance.

“It’s big and meaningful and impactful,” he says. “I don’t think it should be lost on people that there are only 30 to 32 major league teams in each sport in this country, and there will not be many more. Most of them are moving to other markets. Not many are expanding. I see the profound impact on what it means to our community in that sense.”

Third Lake Capital’s Ken Jones says he does not doubt the community’s ability to keep the Rays in the region with a new ballpark.

“This is readily achievable,” he says. “It’s not a question of mine. You have to go after big things, and this is it.”

“There’s a significant amount of momentum,” Hagan adds. “We’re convinced there’s significant corporate support that will make this a successful effort.”

And with that, the Rays are ready to move forward — as Tampa Bay’s hometown team.

“The goal is to win a World Series,” Sternberg says. “If we didn’t think the Ybor City location would put us in a better position to do that we wouldn’t move. We want this stadium to be an icon for Tampa Bay.”