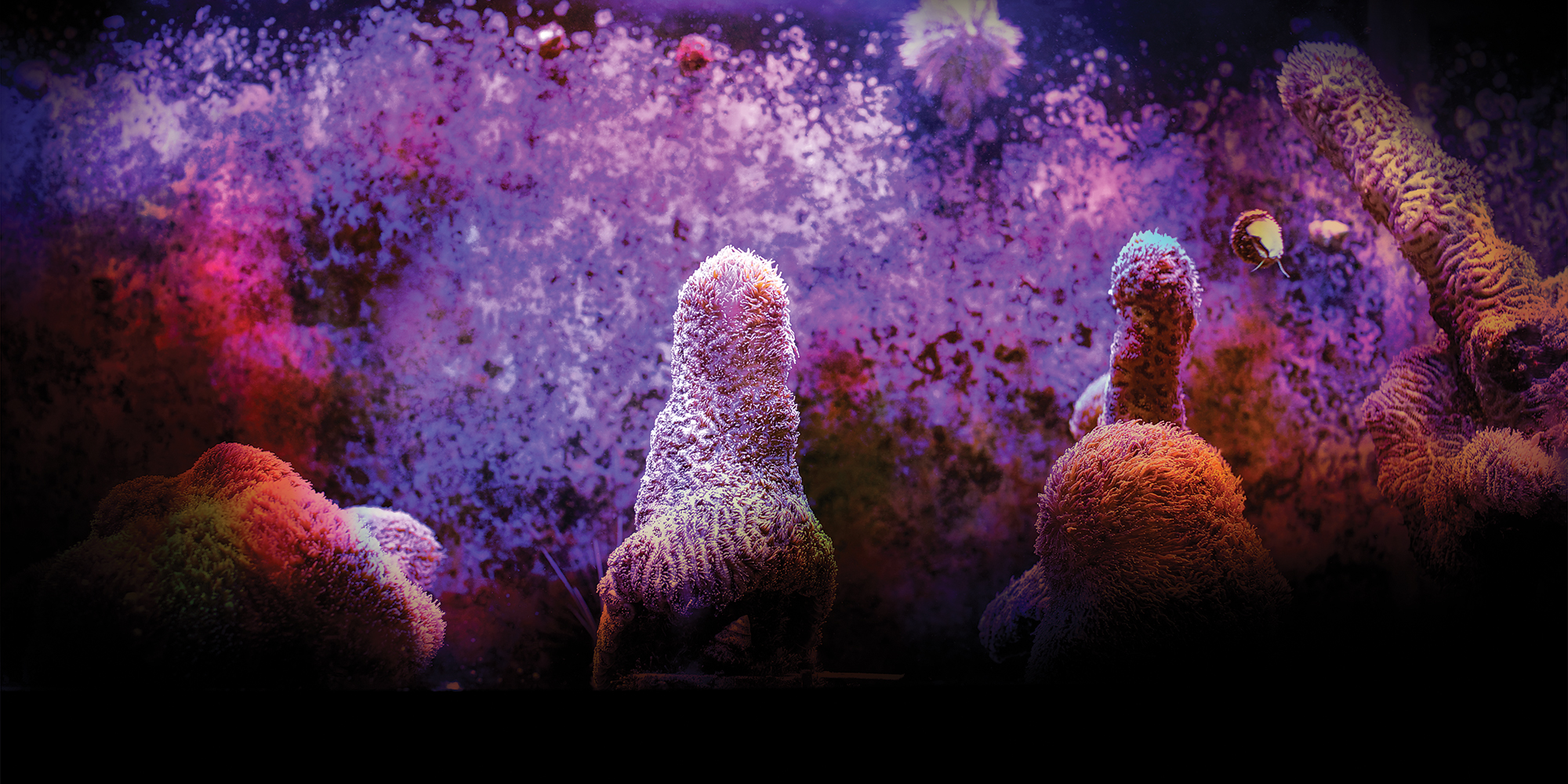

At the Florida Aquarium’s Center for Conservation in Apollo Beach, dozens of Atlantic pillar corals sit in bathtub-sized tanks, bathed in blue light. Tiny polyps extending from their skeletons sway like grass, as shrimp, snails, and sea urchins roam the tanks in search of food. Each creature fills a particular niche in an artificial ecosystem designed to mimic (and mend) Mother Nature.

In August, Florida Aquarium scientists became the first to spawn an Atlantic coral species — specifically, the threatened pillar coral — within a laboratory setting, using cutting-edge techniques to replicate real-world conditions. The milestone could play a critical role in restoring the Florida Reef by repopulating coral communities after decades of decline.

“The Florida Reef Tract [along the state’s southeastern coast] is the third largest reef tract in the world,” says Roger Germann, CEO of the Florida Aquarium. “It’s America’s Great Barrier Reef. There hasn’t been much public attention paid to it, but there’s now a big push to save this reef tract.”

Like many reef systems around the world, the Florida Reef is suffering the dual threats of climate change and disease. Ocean acidification weakens corals, while rising water temperatures cause them to expel the symbiotic algae they rely on for food. This phenomenon, called bleaching, can starve and kill corals. As corals die off, reef systems physically fragment and ecologically crumble. Experts estimate that more than 90% of the world’s reefs will be threatened by 2030.

The decline of coral reefs is both an environmental and economic crisis. Often called the rainforests of the sea for their immense biodiversity, reefs harbor millions of species and pump at least $3.4 billion into the United States economy each year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The Florida Reef alone has an estimated asset value of $8.5 billion for southeast Florida.

“The economy and the environment are not mutually exclusive,” Germann says. “The reef really is part of the unique nature, culture and economy of Florida. It’s tough to go out there and see coral that’s dead or bleached”

To address the issue, scientists at the Florida Aquarium sought counsel from coral biologist Jamie Craggs, whose team at London’s Horniman Museum and Gardens became the first to purposefully reproduce Pacific corals in 2013. In January 2019, the Florida Aquarium launched Project Coral, an offshoot of Cragg’s coral reproduction research initiative that replicates his methods for Atlantic corals.

Using specialized lighting and computer-controlled equipment to mimic sunrises, sunsets and moon phases, aquarium scientists trick corals into thinking it’s time to spawn. In August, just eight months after the test subjects moved into their new high-tech tanks, the corals simultaneously released hundreds of thousands of eggs and millions of sperm — right on cue.

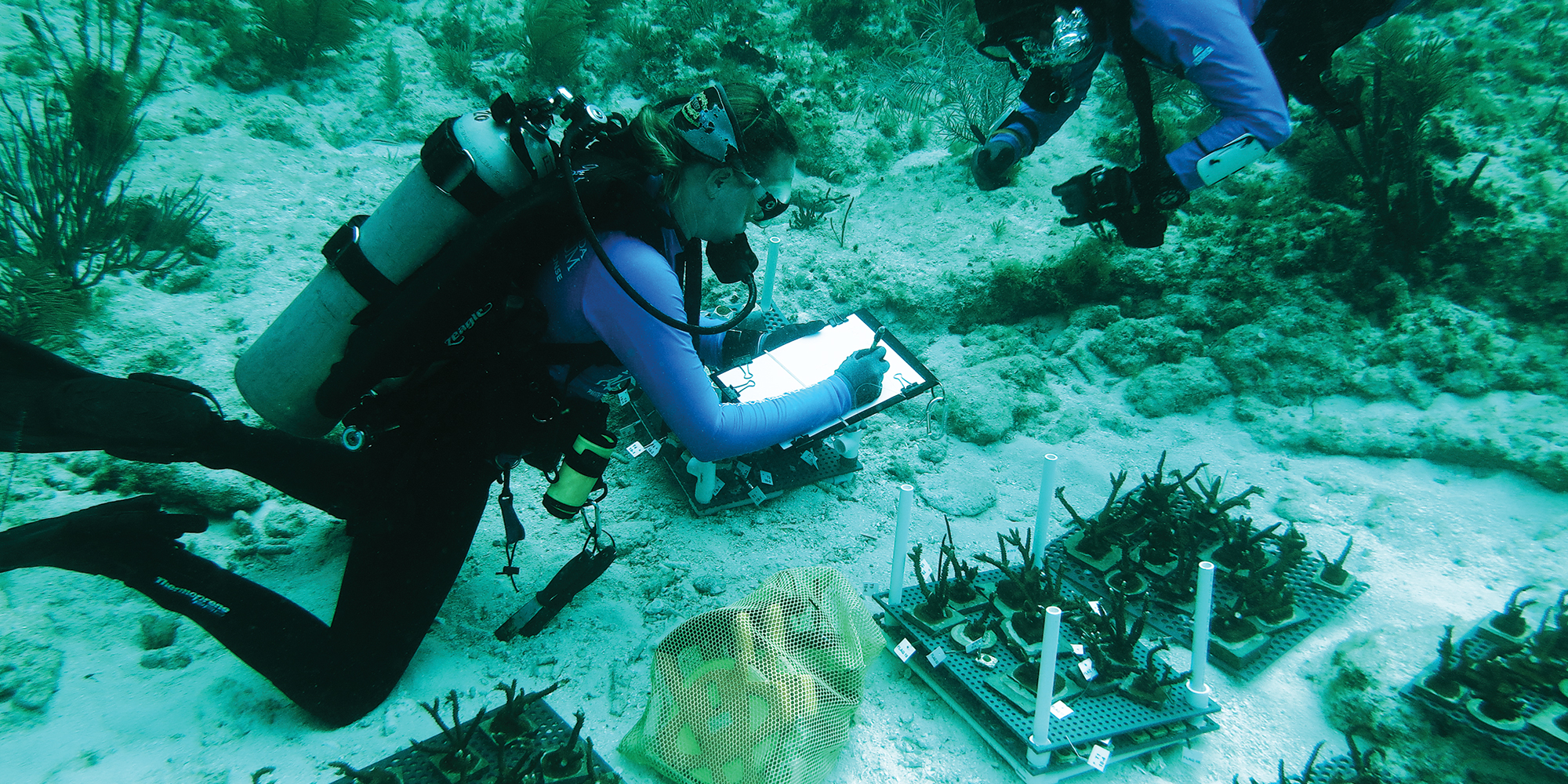

In the wild, spawning events occur just one night each year, which makes collecting wild eggs and sperm a matter of patience, precision and a lot of luck. Artificial spawning, on the other hand, allows for more reliable collection of fertilized eggs. The Florida Aquarium’s scientists will now continue to spawn corals on command, perhaps a few times a year, raising the viable larvae in captivity until they’re strong enough to be planted in the wild.

Although promising, Project Coral is no panacea. Saving reefs requires a multipronged effort to restore coral populations, reduce carbon emissions and find sustainable sources of seafood.

Of the roughly 25,000 larvae produced during August’s spawning, about 2,000 settled onto small ceramic tiles so that scientists could care for them. Just 10% of those settlers are expected to grow big enough for the wild, says Rachel Serafin, a coral biologist at the Florida Aquarium. Even then, not every coral planted in the wild will survive. Those that do survive will help lay the foundation for restoring one of the world’s great reef systems.

“We’ve watched wild coral populations dwindle over decades,” says Serafin. “This research has made it possible for us to get those corals to a suitable age or size before putting them out [in the wild]. It’s like a jumpstart program for coral babies.”