In the years leading up to Prohibition, Tampa was considered among the “wettest” towns in the state. Restrictions brought about by the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution were not greeted with pleasure by many when they took effect in January 1920, prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcohol.

Shortly before Prohibition took effect, 76 saloons were in Tampa, over half in the Latin enclaves of Ybor City and West Tampa, as well as several around the African American business district of Central Avenue and the neighboring Scrub. One of the most popular saloonkeepers during these years was Achilles Cerf, better known as Archer or Archie.

Saloons were virtually outlawed by the Davis Package Law passed by the Florida Legislature in 1915. In their place came “mail order houses,” essentially package stores that sold sealed containers of alcohol. Within a year, there were almost 40 of them in Tampa, including the one that Cerf ran, the South Florida Mail Order House at 101 Lafayette St. (now Kennedy Blvd.).

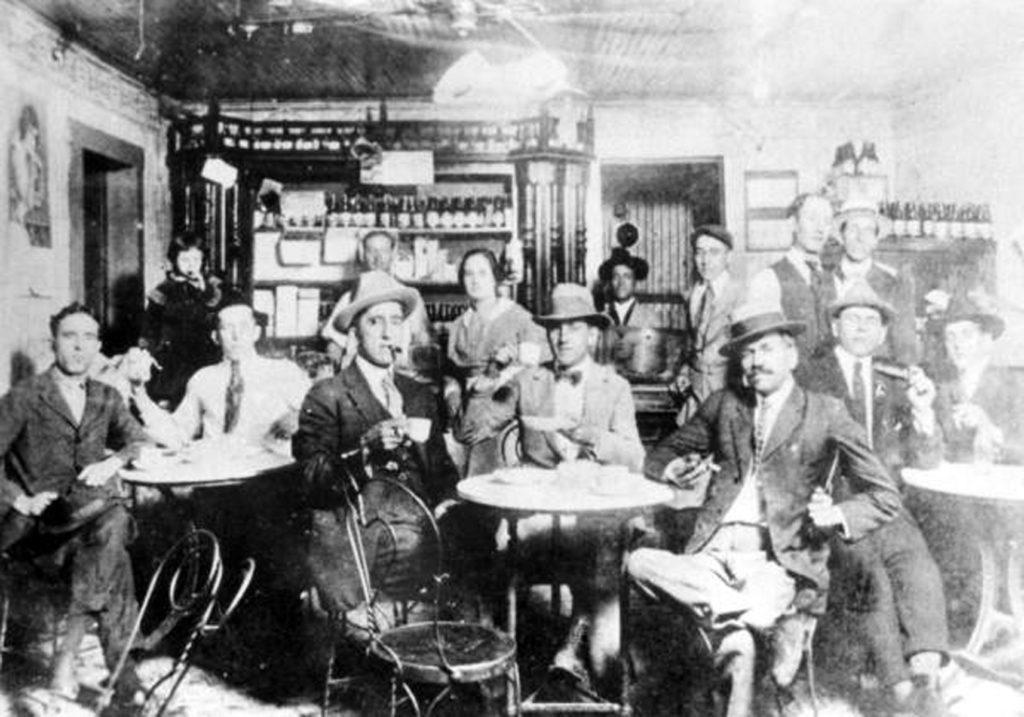

The National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act, helped enforce the 18th Amendment. Undeterred Tampans found ways to circumvent the newest law of the land: making their own booze, buying illegally from bootleggers or obtaining doctor’s prescriptions. Many also turned to speakeasies. The unauthorized bars sprouted up almost overnight, appearing in urban areas like Downtown Tampa, Central Avenue and 7th Avenue in Ybor City, as well as in rural areas throughout Hillsborough County.

Tampa’s business, political and social leadership seemed to mostly turn a blind eye, so finding illicit liquor was an easy task. Still there lived a thirst for a high-class speakeasy for Tampa’s elite, satisfied with the opening of the Eagle’s Club, more commonly known as the Key Club, on Jan. 27, 1927 under Cerf’s general management.

Key Club membership was difficult to obtain. Prospective members had to be invited, meet with the club’s leadership and prove they belonged socially and financially. Plus they had to be trusted with the confidentiality of the club’s existence. It gained its nickname because each member was given a key that would unlock a door at the street level, which would lead to a set of stairs to the club’s entrance on the second floor, where members would whisper a password to the door guard.

The club’s presence was not lost on Tampa Police Chief Dillard York, particularly because the club was located on the southwest corner of Jackson and Franklin streets, less than 100 yards from the police headquarters at Tampa City Hall. Despite the close proximity and the wide knowledge of its presence, York could do little to close the popular speakeasy.

Business at the club progressed smoothly for six months, with the high-end, imported hooch Cerf had been instructed to procure flowing freely. However, the party was about to come to an abrupt end thanks to a crusading judge, an angry housewife and two camera-toting vice cops.

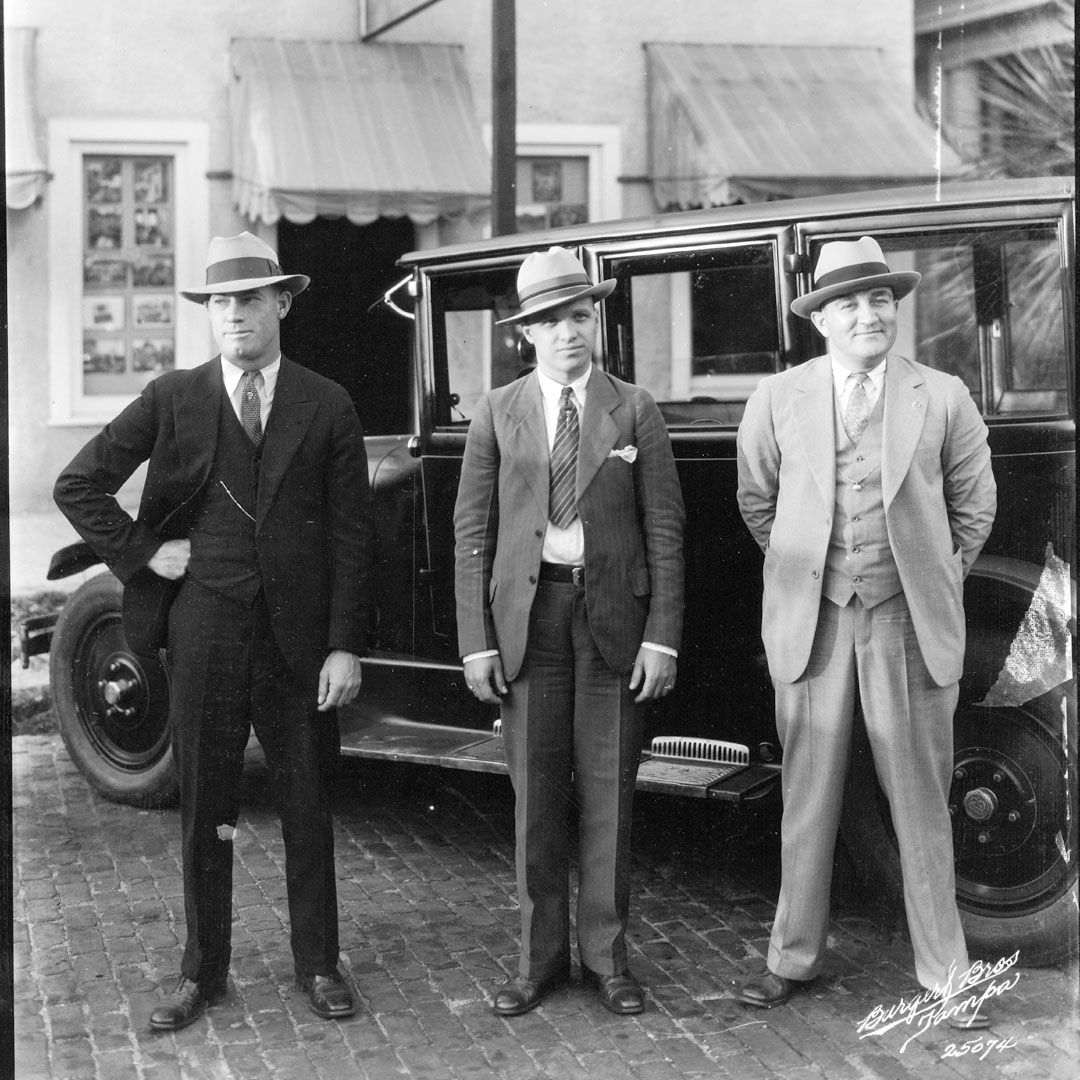

On July 23, 1927, the sanctity of the Key Club was shattered. Tampa police detectives Lawrence Ponder and Harry Myers gained entry into the speakeasy and arrested Cerf, along with the door guard and three waiters. No patrons were arrested at the time.

There are several conflicting stories regarding how the vice cops entered the club. The Tampa Tribune, in its first story about the raid, reported that York received an anonymous letter from a woman whose husband was a member of the Key Club. She was unhappy about the amount of time he spent there and more so about his condition when he came home, so she sent York her husband’s key.

After receiving the letter, York instructed Ponder and Myers to obtain a motion picture camera – no easy task in 1927 – and film the club’s downstairs entrance from an office building across Franklin Street. The detectives did so and in the process captured images of Tampa’s most prominent men.

With the arrest and arraignment of Cerf came a series of legal maneuvers between Cerf’s attorney, C. Jay Hardee, and municipal court judge Leo Stalnaker. Hardee attempted to have Stalnaker removed from the case because of his overzealous attitude and penalties toward Prohibition offenders. Hardee also charged that it was Stalnaker who directed Ponder and Myers to raid the speakeasy. There is no evidence that Cerf was ever tried, much less convicted, for running the Key Club.

On Aug. 28, 1927, a story about the Key Club was printed in the Lincoln (Nebraska) Star. The paper reported that the chief occupant of city hall – Tampa Mayor Perry Wall – openly admitted his Key Club membership, saying Prohibition violated the 14th Amendment by denying citizens their rights to life, liberty and property.

National Prohibition ended in December 1933, and following the repeal of state Prohibition with the ratification of the 21st Amendment in 1935, Cerf was one of a dozen applicants for a city liquor license under Tampa’s new licensing program. Happy days were here again.

Rodney Kite-Powell is a Tampa-born author, the official historian of Hillsborough County and the director of the Touchton Map Library at the Tampa Bay History Center, where he has worked since 1995.

Read more Tampa Bay history here.