In many ways, the cigar factories that dot the Ybor City landscape are identical.

They were all built with red brick. Each stands three stories tall and has a basement. The buildings run east to west according to the sun’s daily path — with no electricity, cigar workers needed as much natural sunlight as they could get.

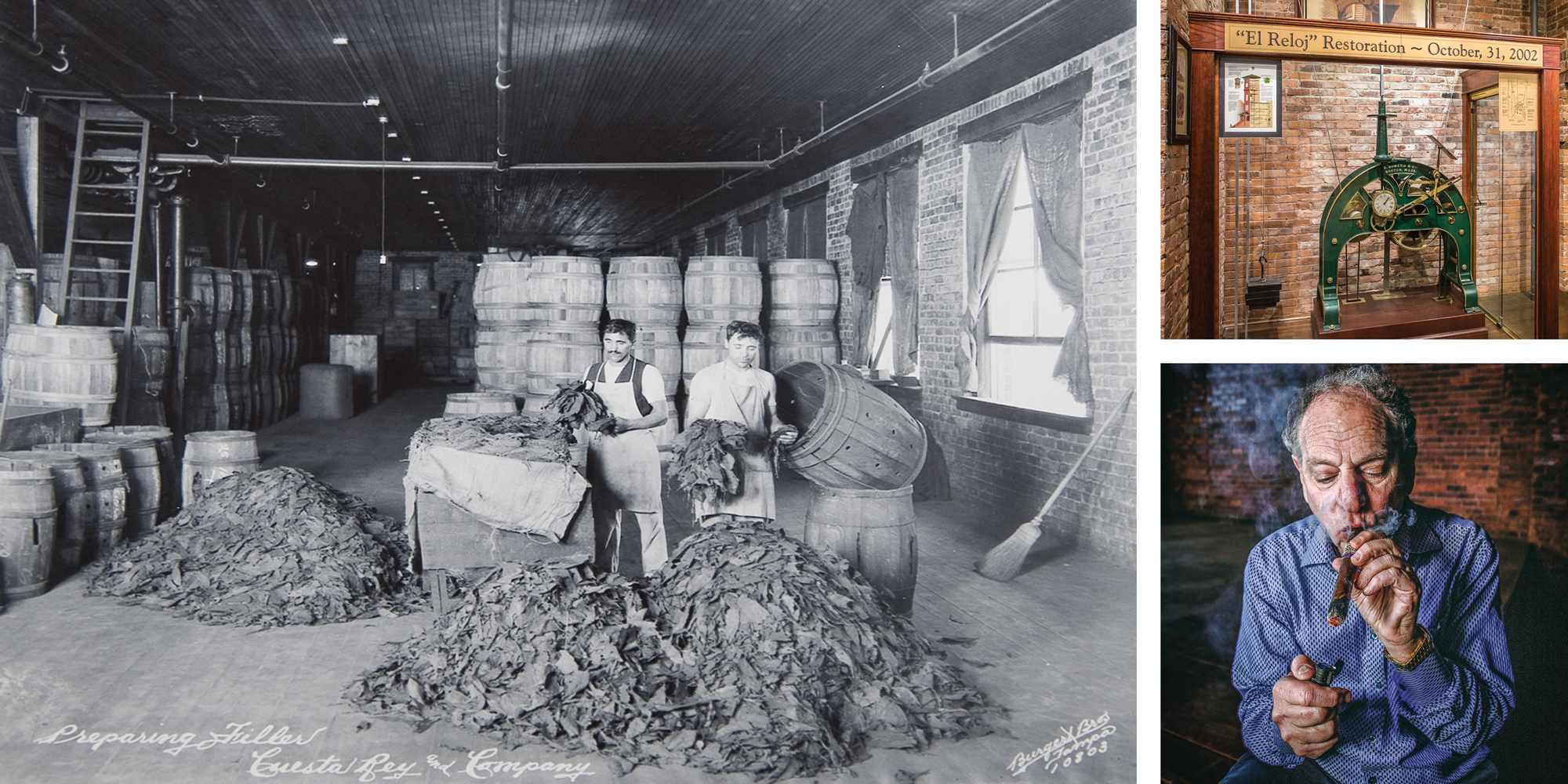

But look a little closer, and you’ll notice one major difference. The factories are no longer functioning, no longer producing the cigars that put Tampa on the map. The exception? El Reloj, named for the thundering clock that used to ring out across all of Ybor City each hour, keeping time for the neighborhood. The factory is home to the 123-year-old J.C. Newman Cigar Company, the only family-owned premium cigar manufacturer left in the entire United States.

“We used to be able to get on our roof and see all of our competition all over the United States from our roof because Tampa was the fine cigar capital of the world,” says company president Eric Newman. “My grandfather went into business for himself in 1895. When he started, there were 42,000 licensed cigar manufacturers. We’re the only one of those cigar manufacturers from 1895 that are still owned and operated by the founding family.”

Like essentially every other red-blooded American industry, the cigar business is a shadow of what it was when Hungarian immigrant Julius Caeser Newman became a cigar apprentice at 15 years old in the early 1890s in Cleveland, Ohio. Just three years later, his mother secured an order for 500 cigars from the local grocer, and Newman started the business that exists today out of the family barn.

In a sign of things to come, the fledgling company’s first real challenge came when, after moving operations into the heated basement of their home, Newman’s mother evicted the business. The cigar production process, she discovered, had made her canned fruits and vegetables taste unmistakably of tobacco. Newman moved his company into a storefront, and later a factory, in down-town Cleveland, where he found ways around a series of threats to his business. First, millions of Americans were introduced to cigarettes when shipments were sent to the troops fighting overseas during World War I.

“Until World War I, no one smoked cigarettes. Cigars were the tobacco of choice for everybody,” Eric Newman says. “All our customers who were in Germany who were cigar smokers came back as cigarette smokers.”

Newman’s grandfather lost money during the Great Depression, when he kept two factory shifts running each day just to keep people employed. The same happened after World War II, when the federal government returned the cigars it had purchased from the Newman Company during fighting — 35 percent of the factory’s total wartime production to help stimulate the economy — with the company taking a total loss. In the immediate post-war years, more cigars were coming back into the factory than were being produced each day.

Those issues were temporarily solved with Newman’s development of the Cameo cigar, which cost just a nickel each and became one of the country’s top-selling cigars. The success was short-lived; Newman raised the cost to six cents, and business plummeted. Simultaneously, a tobacco price-fixing scheme by the larger cigar manufacturers made it nearly impossible for the Newman Company to stay competitive in the mass-market cigar business.

“We had to find a niche in the cigar business that the big guys weren’t in,” Eric Newman says. “In the early ‘50s, they were in the mass market business, so my grandfather said we should get in the premium business. There was only section of the Unit-ed States making premium cigars in the early ‘50s, and that was Tampa, Florida.”

In 1954, at 78 years old, J.C. Newman moved his entire operation to the current Ybor City factory. Less than a decade later, he watched as many of his fellow Cigar City manufacturers shuttered, unable to overcome the embargo on the Cuban tobacco they depended on for the Havana-style cigars Tampa had become known for. Thanks in part to a partnership with Carlos Fuente and his company (Fuente would produce handmade Newman cigars at his factory in Nicaragua, and New-man would make, market and sell U.S.-made Fuente cigars), Newman, his son Stanford, and later his sons Eric and Bobby, would ride out the peaks and valleys of the cigar industry through the 1990s. Today, the Newmans produce the majority of their hand-rolled and machine-made cigars at their factory in Nicaragua, including their iconic Cuesta Rey (the name that still shines from the top of El Reloj) and Quorum, a newer cigar that is now the world’s top-selling bundled ci-gar. In Ybor City, more than 100 workers churn out 60,000 cigars made both by machine and by hand every day.

The past decade, though, brought a new adversary, and one that poses the greatest threat to the business so far: the federal government.

In 2016, the Food and Drug Ad-ministration declared it would regulate all tobacco products, including premium cigars like the ones made by the Newmans, in an effort to curb tobacco use by kids and teenagers. The Newman company had been anticipating the move for about a decade and had already been working with politicians from both parties to block it. Sen. Marco Rubio, former Sen. Bill Nelson and Rep. Kathy Castor have all unsuccessfully sponsored federal legislation exempting premium cigars from FDA regulation — a costly proposition that would involve new taxes and new standards to meet, very likely putting the Newman Company out of business. Eric Newman says his family’s business is an “unintended consequence” of the government’s efforts to keep kids away from more youth-oriented tobacco products like flavored cigarettes, Juuls and other e-cigarettes.

“We’ve explained to them, we’re David going up against Goliath. We’re a threat to no one,” he adds. “We go up to Congress, and we don’t ask them for an earmark. We don’t ask them for a tax credit. We just ask them to leave us alone.”

The main argument for exempting premium cigars is based on their relatively low rate of use. A 2017 study in the journal Nicotine & Tobacco Research established smokers smoked a median number of just 0.1 premium cigars per day, compared to a median of 10.1 cigarettes smoked by established cigarette users, and 1.6 filtered cigars. In addition, the median age of first use for premium cigars is 24 years old, supporting the Newmans’ assertion that kids aren’t smoking premium cigars.

“Cigars are an adult choice,” Newman says. “People smoke cigars because they enjoy them like they enjoy a glass of wine. It’s a custom industry.”

In March 2018, the decision to bring premium cigars under FDA oversight was put on hold by the Trump administration, which opened up the issue for public comment. According to Newman, more than 34,000 comments critical of the regulations were submitted. Newman says he’s heartened by the community’s support of the city’s namesake.

“This is the Cigar City. If you know anybody who has lived here for four generations or more, chances are someone in their family worked in the cigar industry because those were the jobs around,” he says. “People rallied to the cause. We’re still fighting it. We aren’t there yet. We aren’t go-ing away, but we’re still fighting.”

“God willing we’ll be here for another 123 years.”