Beginning in the mid-2010s, the long-awaited renaissance of Tampa Heights was finally taking hold. For there to be a renaissance there has to have been an earlier decline, and to say that Tampa Heights was once in decline would be putting it mildly. The neighborhood just north of Downtown Tampa was the city’s first suburb, but it also became one of the city’s first economically challenged areas.

The rise, fall and rebirth of Tampa Heights is a story that includes an epidemic with mysterious origins, a short-lived town government and grand residences, followed by long-lasting economic decline and a slow path to recovery.

During Tampa’s numerous Yellow Fever outbreaks in the mid- to late-19th century, many families fled to the sparsely populated “heights,” just north of today’s Downtown Tampa. It was seen as a healthy alternative to living in “town,” i.e. Tampa. Though unknown at the time, mosquitos were responsible for the spread of the disease, and the slightly higher elevation allowed for better drainage and fewer mosquitos. That, combined with the fact that few people lived there at the time, gave the “heights” the perception of being a healthier location.

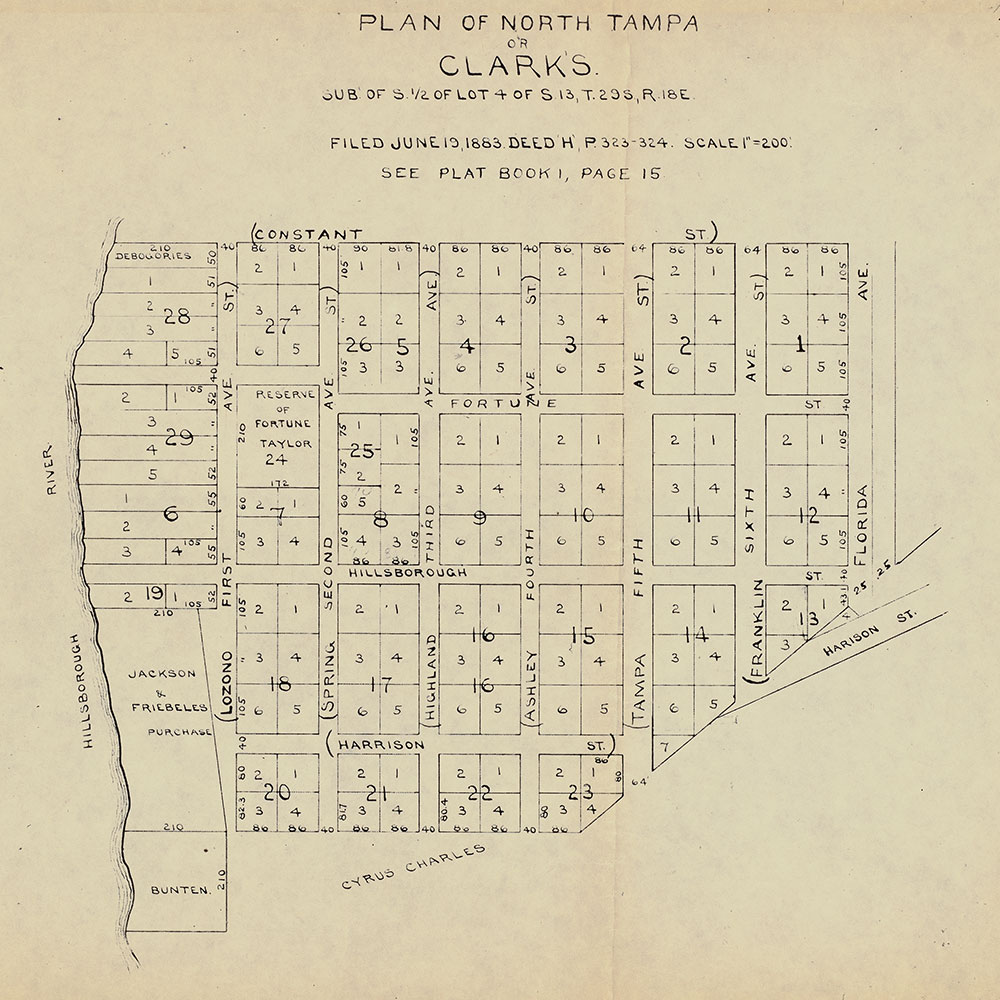

In the 1880s, Tampa began to grow after the arrival of the railroad, discovery of phosphate, and the beginning of the cigar industry. At the same time, a new town was incorporated in the heights area north of Tampa. This new town was dubbed “North Tampa,” the first use of this long-lived term. The boundaries of the Town of North Tampa included Constant Street (roughly today’s Laurel Street) to the north, Florida Avenue to the east, the Hillsborough River to the west, and just north of Harrison Street to the south.

Though it was not much more than a continuation of Downtown Tampa’s north-south streets, the property did lie outside of Tampa’s corporate limits, so it was eligible to become its own town. The town plat (map) was created for E. A. Clarke in 1883. On November 8, 1886, North Tampa was officially incorporated, and a town mayor and council were elected. Almost everyone involved in North Tampa was already part, or would soon become part, of Tampa’s political and economic power structure.

Ironically, the person who originally owned the land occupied by the new town of North Tampa sat outside of that power structure, both because of race and gender. Fortune Taylor, an African American woman, owned 32 acres of land north of Tampa, which she acquired through a federal land grant in 1875. She sold most of that land to Edward A. Clarke, a prominent Tampa businessman, and his son-in-law A. J. Knight, in the mid-1870s, retaining just under an acre for her home site (located on the south side of Fortune Street, near today’s Barrymore Hotel).

While Clarke and Knight were subdividing their land and creating a new town, cattleman and businessman William B. Henderson was acquiring his own property for a new subdivision that he named Tampa Heights. The neighborhood, located just to the east of Clarke’s North Tampa, was small (just six blocks bounded by Florida and Central Avenues and Oak and Henderson Avenues), but the name caught on. Soon, the entire area north of downtown was known as Tampa Heights.

The town of North Tampa ceased to exist in 1887 when, along with adjacent land, it became the Second Ward of the new City of Tampa. As Tampa continued to grow, Henderson’s Tampa Heights grew along with it. Ultimately, the Tampa Heights neighborhood encompassed everything north of downtown and south of Buffalo (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard), and between the river and Nebraska Avenue.

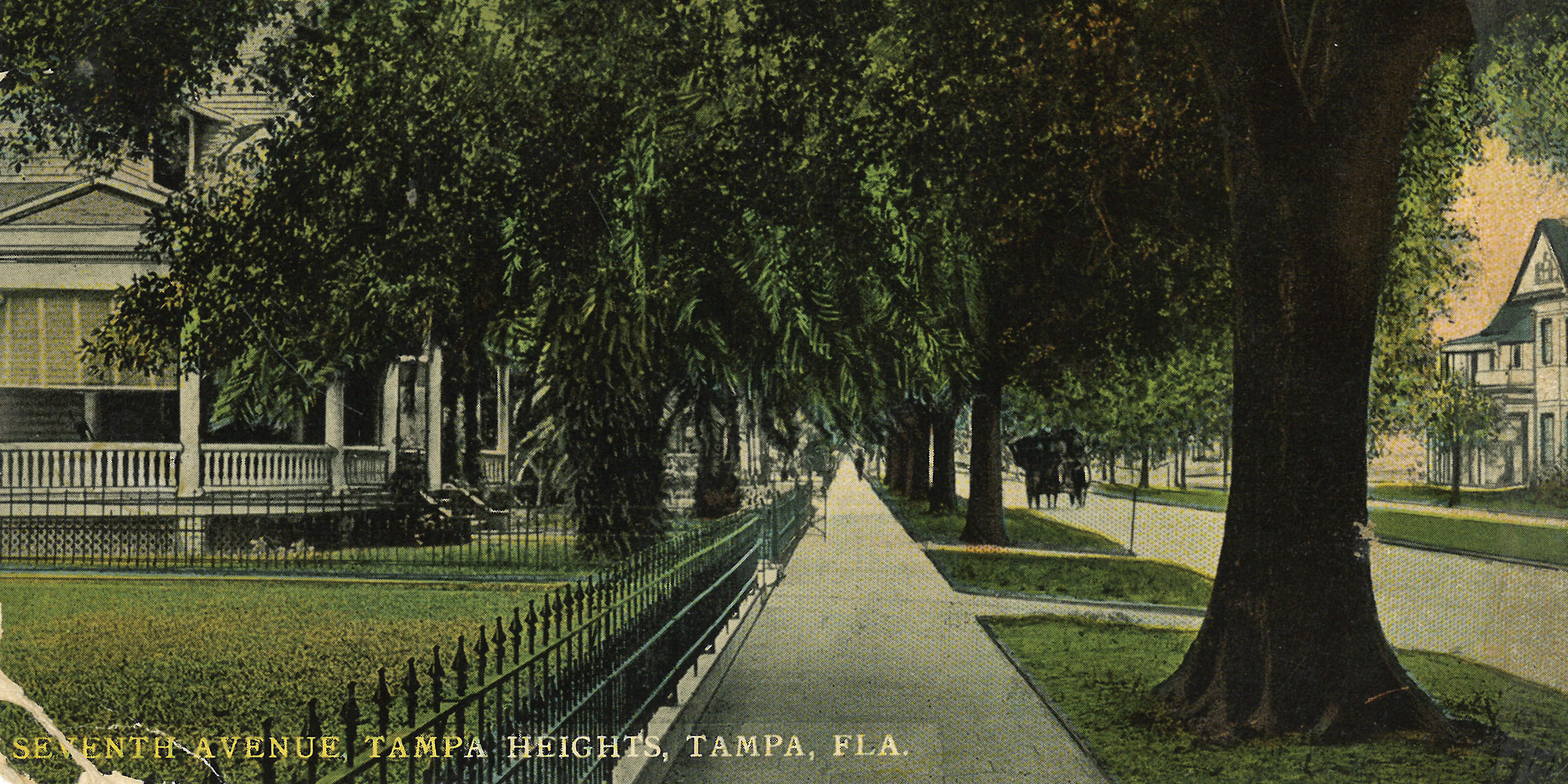

By the 1890s, Tampa Heights was becoming the preferred place to live for wealthy residents. Elaborate Victorian homes were built throughout the neighborhood, with special emphasis along Ross Avenue, Palm Avenue and Nebraska Avenue. Businesses opened on Franklin Street, providing a continuity between Tampa Heights and downtown. The city constructed its waterworks facility near the river and Seventh Avenue in the early 1900s, followed by the Tampa Electric Company’s streetcar barn a few years later. Despite the addition of these more industrial structures, Tampa Heights was still viewed as a popular place to live

Tampa’s African American elites also called Tampa Heights home, but they were restricted in where they could live. While Lamar Avenue was among the main residential streets for African American professionals during this time, there was an unwritten rule that they could not live north of Kay Street or west of Jefferson.

Then, as Downtown Tampa continued to grow during the 1910s and 1920s, the popularity of Tampa Heights actually began to wane. Subsequent generations chose to live in Hyde Park, Palma Ceia, Davis Islands, and other nearby neighborhoods, leaving behind Tampa Heights and its once grand residences. Some of those homes were donated by families to social service providers. There was a desperate need for charity services during this time, as government support for the poor was not nearly as prevalent as it is today. The intent of the families and the charities was pure, but the unintended consequences had far-reaching effects. With the neighborhood already declining in popularity, fewer middle-class families desired to live near these social service providers. A number of the neighborhood’s large homes were soon divided into rooming houses and halfway houses for people who could not find or afford other housing options.

Many of Tampa’s older neighborhoods joined Tampa Heights in economic and structural decline following World War II. The G. I. Bill afforded veterans the ability to purchase new homes in the suburbs, but they could not use that money to renovate existing structures. With new homes and new subdivisions the order of the day, Tampa Heights slipped further into decay.

Beginning in the 1970s, the historic preservation movement began to show the value in older neighborhoods. Locally, Hyde Park and Ybor City became the focus of preservation efforts, with Hyde Park in particular experiencing the most positive effects. Local preservationists thought that the same thing could and would happen in Tampa Heights. The neighborhood received both national and local historical designations, which offered tax incentives in exchange for protection from demolition. Still, it took far longer for Heights to feel the same bump that boosted Hyde Park.

Finally, in the early 2000s, the situation began to change. Investments by large companies and small entrepreneurs began to make a difference. Small steps became big leaps, and eventually major redevelopments and preservation initiatives took hold. An old storefront, the TECO streetcar carbarn, and the city’s old waterworks building became The Hall on Franklin, Armature Works and the Heights Public Market, and Ulele. Craft breweries and restaurants filled empty buildings. New construction rose in long-deserted lots and historic homes started to gain new lives.

These successes have come at a price. Rising property values have pushed out longtime residents, and there is often an apparent socioeconomic and cultural divide between those visiting the trendy bars and restaurants and those utilizing the social services that remain in the neighborhood. These are the issues that any growing city must face. Is there room for everyone in the reborn Tampa Heights? Only time will tell.

Rodney Kite-Powell is the Director of the Touchton Map Library at the Tampa Bay History Center, where he joined the staff in 1995. He received a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Florida and a Master of Arts from the University of South Florida, both in the subject of U.S. history. Born and raised in Tampa, he has written and lectured extensively on the history of Tampa, Hillsborough County, and Florida. He was recently named the official historian for Hillsborough County by the board of county commissioners.

Want to learn more? Check out The Rise of Seminole Heights