With all apologies and due regard to Ybor City, West Tampa should be known as “Cigar City” since it was (unlike Ybor) an independent municipality for 30 years. West Tampa owes its creation to both the cigar industry and to the Macfarlane Investment Company headed by Hugh Macfarlane.

Born near Glasgow, Scotland, in 1851, Hugh Campbell Macfarlane moved to Tampa in the mid-1880s and opened a law practice. In 1887, as a city and state’s attorney, he helped reincorporate the city of Tampa and began purchasing several hundred acres of land on the western bank of the Hillsborough River. Then, beginning in 1891, thanks to generous loans and land grants, Macfarlane and his partners enticed cigar factory owners to relocate their businesses from cities like Key West and New York. The new city of West Tampa was incorporated on May 18, 1895, with over 2,000 residents, most of them newly arrived Cuban and Spanish immigrants who came to work in the cigar factories.

At first, West Tampa’s population largely consisted of young men working in the cigar factories, and the city’s location was fairly isolated from the adjacent city of Tampa. The eastern end, near the river, was also quite swampy. Because of this, West Tampa was called everything from a Wild West town to an alligator hole; the area was first nicknamed La Caimaneria, or “place of alligators,” by the city’s Latin residents. Traveling around the neighborhood was difficult. While Macfarlane extended the Tampa streetcar line to West Tampa, it was not until 1903 that the West Tampa City Council began paving its streets, first with clay from the city of Bartow and later with bricks. Earlier, in 1893, Macfarlane constructed a bridge over the Hillsborough River near Arch Street on the west side and Fortune Street on the east side to connect West Tampa to the northern part of the city of Tampa. The Fortune Street Bridge is in the same location today, but the current structure was built in the 1920s.

Since West Tampa was a separate municipality from the city of Tampa, it could (and did) have its own street names. Some of the north-south streets served as continuations of those in Hyde Park to the south, while most of the others were new. Hugh Macfarlane filed the original plat for West Tampa in 1893 and named two of the main north-south streets for his family — Frances for his wife and Howard for their young son. The third important north-south street was named Armina after the Macfarlane-owned Armina Cigar Factory. Main Street, as the name implied, was the main east-west thoroughfare. The east-west streets to the north of Main Street were all named after trees, from Laurel on the south side to Beech on the north.

If some of these names do not sound familiar, it is because some of them have been altered or changed altogether over the past 127 years. The oddest change turned Armina into Armenia, launching the incorrect assumption that West Tampa had an Armenian population at some point. Though the exact reason for the change is not known, it is thought that it stemmed from a spelling error on an early street sign. Frances was often misspelled as Francis, possibly because of the existence of a Frances Street in Tampa Heights. The West Tampa Frances/Francis became an extension of Albany Avenue when West Tampa was annexed into the city of Tampa in 1925. Two other streets, Beech and Greene, became Beach and Green at some point.

The city of West Tampa’s initial growth was rapid. By 1900, the population had eclipsed that of Tallahassee, and by 1912, it was Florida’s fifth-largest city, with 8,258 residents. Almost half of the residents of the Tampa area, including West Tampa, were immigrants or had at least one foreign-born parent.

The large immigrant population caused some concern for Tampa’s Anglo white elite, though they seemed to favor West Tampa over Ybor City, at least initially. This was likely because of the number of white businessmen involved in West Tampa city government, which would limit the political power of the larger Cuban population — viewed as a potential threat because of their vehement pro-labor and anti-capitalist beliefs as well as the racial attitudes of the era. There were several Cubans in the government, too, and they were occasionally targeted by white vigilante groups.

The most sensational example was the 1902 kidnapping of West Tampa mayor Francisco Milian. In addition to being mayor, Milian was the lector at the Bustillo Brothers and Diaz cigar factory. He was offended by the factory owners’ violation of the unwritten rules regarding the lector system. The main issue centered around how Milian was to be paid. Tradition dictated that lectors were paid by the workers inside the factories, but the factory owner demanded that Milian had to wait and be paid outside on the sidewalk. Milian refused this and told the workers he would not read to them. The workers, in turn, went on strike in support of Milian.

On Saturday afternoon, Nov. 1, 1902, Milian left the West Tampa city hall and got into a carriage with three men. He was taken out “to the country” and beaten by a group of vigilantes. He was then given a choice: leave the area immediately — and permanently — for Cuba or be killed. Milian left for Cuba, but his absence was immediately noticed. A general strike of most cigar factories in both West Tampa and Ybor City soon commenced, and Milian returned to Tampa to a hero’s welcome. Rather than face execution, Milian returned to his seat in the lector stand in the Bustillo factory and behind the mayor’s desk in West Tampa’s city hall.

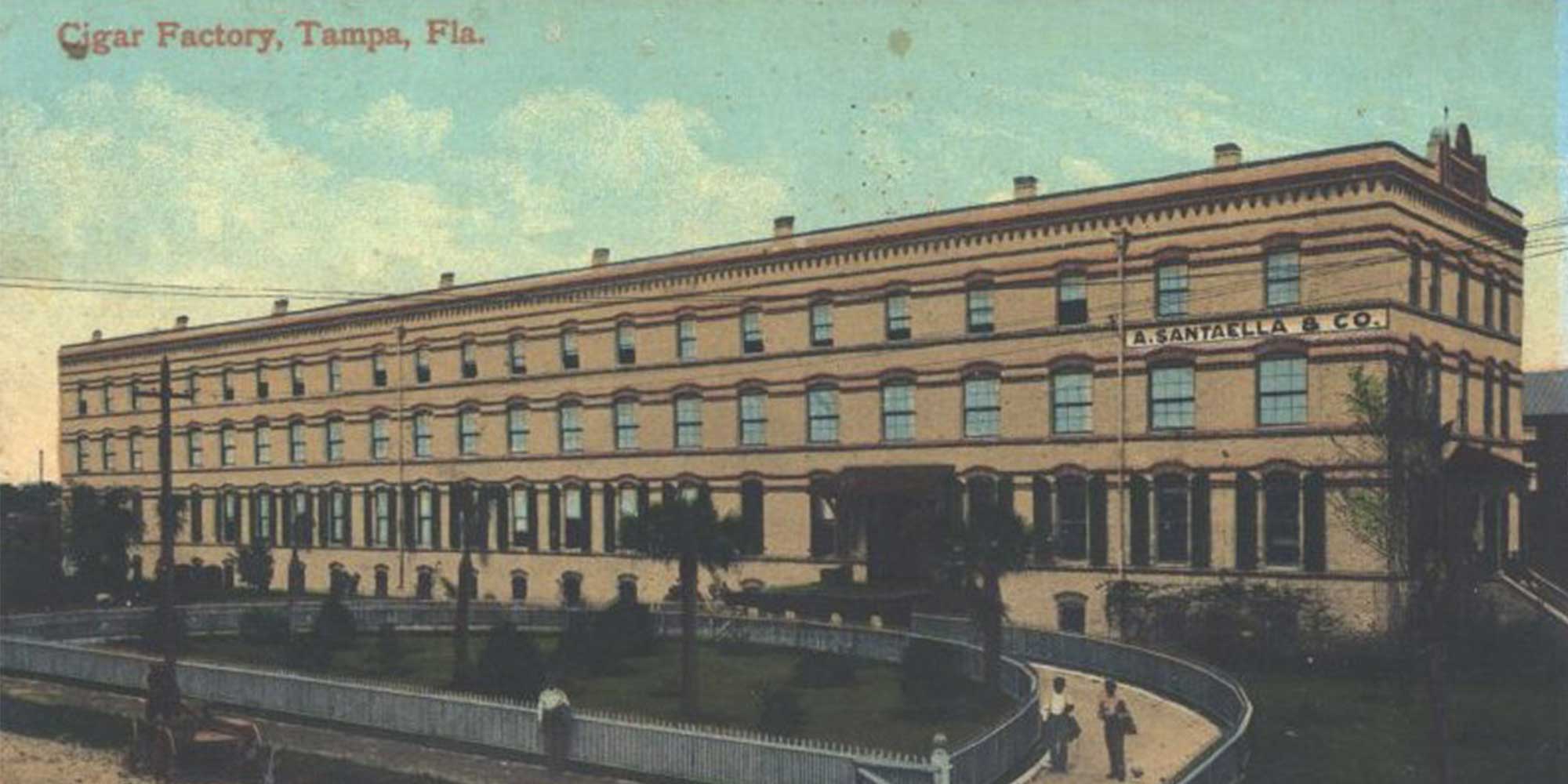

Incidents like that one show how directly the economic health of West Tampa was tied to that of the cigar industry. The area was home to a number of large factories such as Cuesta, Rey & Co.; A. Santaella; Morgan Cigars; Monne Brothers; and O’Halloran. At its peak during the 1920s, West Tampa had thousands of residents and over 100 cigar factories of varying sizes. The city of Tampa, eager for increased population numbers and tax revenue, then annexed West Tampa. The independent city ceased to exist at midnight on Dec. 31, 1924.

The following decade was not kind to Tampa’s cigar industry. The Great Depression reduced the demand for quality cigars, and the introduction of machines made the cigar-making craftsman a dying breed. Following World War II, returning soldiers used money from their GI Bills to build new homes in the growing suburbs rather than repairing older homes in their childhood neighborhoods (as the federal money could only be used for mortgages, not improvements or additions). For former West Tampeños, their new neighborhoods included everything from South Tampa to Town & Country and later Carrollwood.

In the 1970s, Interstate 275 (then designated as Interstate 4) cut through West Tampa, contributing to the degradation of the surrounding neighborhoods. Despite these obstacles, West Tampa and its residents persevered. While a few buildings still house small cigar-making operations, new uses have been found for the historic factory buildings, from office space to loft apartments. West Tampa’s business district, centered on Howard and Main, remains active to this day, and Cypress Street, originally an industrial thoroughfare, may become a high-speed corridor connecting downtown Tampa to the Westshore area. Now, the challenge becomes preserving the unique culture and architecture of West Tampa while it continues to change and grow.