Sometime soon, take a walk down Ybor City’s Seventh Avenue. Not a buzzed stagger at night, mind you (though that can have its own allure), but a stroll on a nice day. You will see brick buildings, some constructed near the turn of the last century, and the famed mutual aid societies, which revolutionized both the immigrant experience and the health care system. You will see dozens of restaurants, many claiming to have the best Cuban sandwich and most authentic Spanish bean soup. And you will be doing all of this in one of only two National Historic Landmark Districts in the state (the other is St. Augustine). How did it all happen? They say it started with guava trees.

As the story goes, Gavino Gutierrez was into guavas. More specifically, he was an importer who worked for a company in New York that sold guava paste and jelly. The company’s owner had heard that there was a wild grove of guava trees near Tampa, and in 1884, he sent Gutierrez to investigate. He did not find the fabled grove, but he did find an interesting town with a lot of potential. Gutierrez then continued on to Key West, where he shared what he learned with a few friends, all of whom were cigar manufacturers.

The guava story may be more myth than reality, but Gutierrez did travel from New York to Key West by way of Tampa, and one of those friends was Vicente Martínez Ybor. He owned a large cigar factory in Key West, but he was unhappy with the island city. His workers went on strike too often, and they were too close to their native Cuba, making them prone to leave for home if and when things became difficult.

Martínez Ybor’s friend, Ignacio Haya, had a factory in New York with his business partner, Serafín Sánchez. Labor problems were less of an issue in New York, but the cold winters and lower humidity made working year-round problematic. Both cigar manufacturers had solicited offers to move their factories from other cities along the Gulf Coast, including Pensacola, Mobile and Galveston. Gutierrez convinced them to give Tampa a chance. Martínez Ybor, Sánchez and Haya liked what they saw.

In October 1885, Martínez Ybor was ready to purchase enough land to move his cigar factory from Key West and begin a new company town. The area he chose was northeast of the town limits of Tampa, a tract owned by John T. Lesley, a prominent Tampa businessman and cattle rancher. Lesley wanted $9,000 for the land, but Martínez Ybor knew he paid only $5,000 for it a few months earlier. The two reached an impasse, and the newly formed Tampa Board of Trade stepped in to seal an agreement. Formulated by board member William Henderson, the settlement called for Martínez Ybor to pay Lesley’s price, then receive a $4,000 reimbursement from the board. The board also assured Martínez Ybor that they would do all they could to keep organized labor out of Tampa. The parties agreed, and Martínez Ybor purchased Lesley’s land. Gutierrez and the Sánchez and Haya partnership purchased several adjacent acres of land.

The land that would soon become known as Ybor City was mostly pine forest, but the southern edge was a salt marsh. The new owners dumped tons of sand to build up the land, reshaping the coastline in the process. Plans were drawn up and construction started on Martínez Ybor and Haya’s factories. Houses, stores and restaurants were built soon after. By 1899, there were nearly two dozen cigar factories in Ybor City, a brewery (the first in the state), plus a growing business district along Seventh Avenue. Perhaps more importantly, the cigar industry, along with the railroad and phosphate, boosted Tampa’s population from 720 in 1880 to 15,839 in 1900 — including thousands of Cuban, Spanish and Sicilian immigrants.

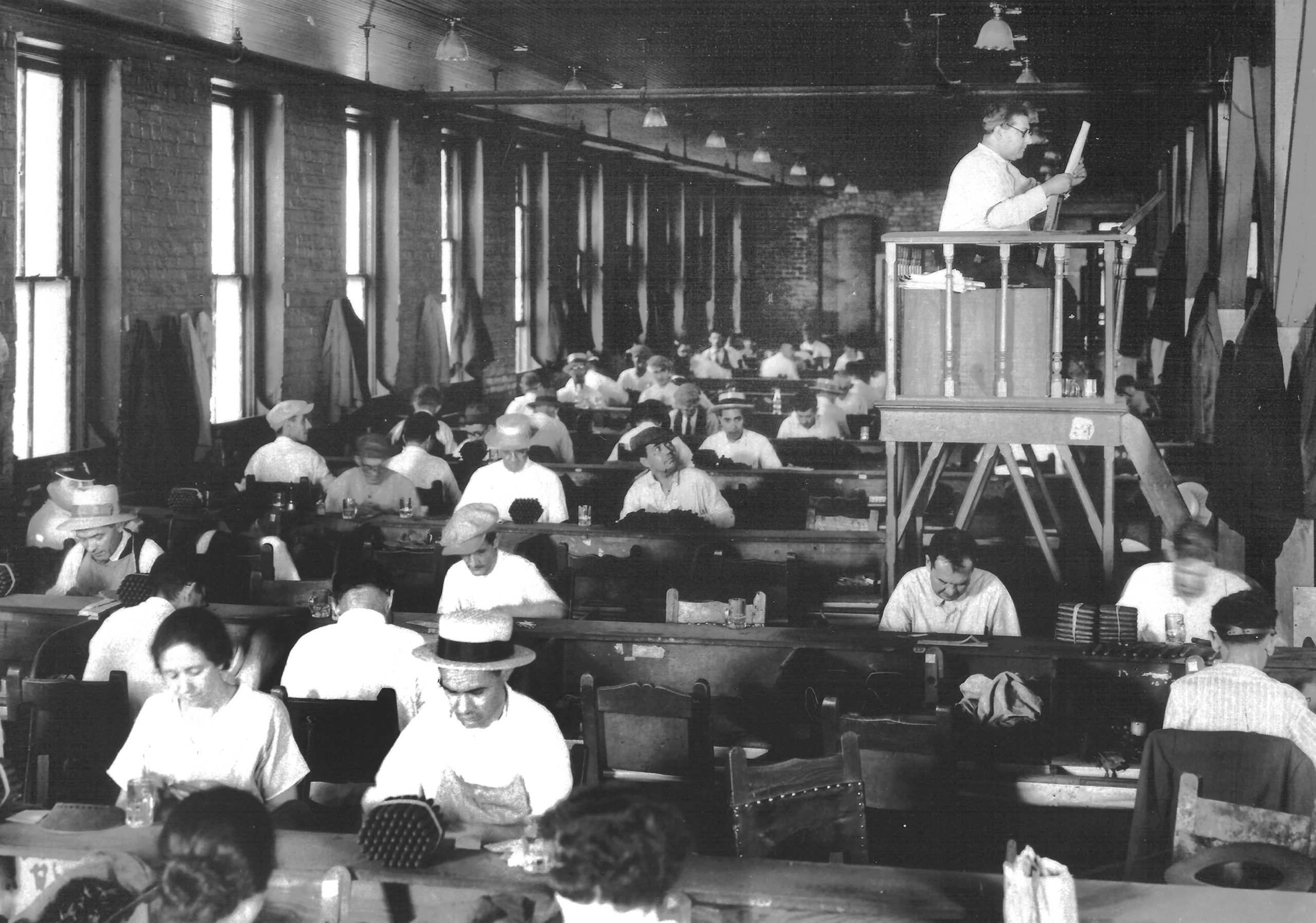

Ybor City’s true heyday was during the 1910s and ’20s. It is hard to imagine how widespread cigar smoking was 100 years ago, but that popularity supported an industry that in turn supported an entire city. Over 400 million cigars were produced by hand every year in Ybor City during the 1920s.

One of the more unusual, but very important, parts of Ybor City’s culture was the system of mutual aid societies. Each immigrant group had its own club: El Círculo Cubano for white Cubans, Sociedad La Unión Martí-Maceo for Afro Cubans, the L’Unione Italiana for Sicilians, and two Spanish clubs — Centro Español and Centro Asturiano, for Spaniards who came from Asturias. There was also a German-American Club, but its location on the border between Ybor City and Tampa Heights showed how that immigrant group spanned both neighborhoods.

The mutual aid societies worked as a bridge for immigrants struggling to adapt to their new homeland. They provided a great social outlet and an even greater service through the clubs’ medical clinics. Both the Centro Español and Centro Asturiano operated full-size hospitals. Medical care was provided through club dues. But this amounted to socialized medicine, and it was shunned by the Anglo medical establishment. Doctors who practiced in the clubs’ hospitals and clinics were even barred from belonging to the Hillsborough County Medical Association.

Ybor City’s economy, and the overall cigar trade, were irreparably damaged by the Great Depression. World War II further disrupted Ybor, and the post-war prosperity that enveloped Tampa passed Ybor by. Three more factors, both political and economic, dealt the final physical blows to Ybor. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order that, among other things, banned all Cuban imports — including tobacco. Tampa’s few remaining cigar factories were now without the sole ingredient for their trade.

Following on the heels of the embargo came urban renewal and the construction of Interstate 4, which prompted the demolition of hundreds of structures. Most of the buildings destroyed were small, single-family homes (the familiar shotgun house still seen in Ybor City and West Tampa), but other important buildings were also torn down, including the historic Ybor City fire station and the headquarters for the Martí-Maceo club. Though done in the name of progress, this all had the opposite effect and contributed to Ybor’s continued decline.

Ybor City, particularly along Seventh Avenue, began to see a resurgence in the late 1970s. Artists began moving to the area, and historic preservationists soon saw the benefits of making Ybor a historic district. By the 1980s, a growing bar scene began to bring people back onto Ybor’s streets, and though it has had some growing pains because of that development, Ybor has become a top tourist destination for visitors to the city. The architecture that one sees, and the sights, sounds and smells that one takes in, are all part of Ybor City’s history. The jury is still out on the guavas.