At the heart of St. Petersburg’s downtown core lies a modest building nestled between two of the area’s busiest streets, Central and 1st avenues north.

An unassuming entry welcomes visitors into a glimmering, glistening wonderland of color, shape and form. Transparent, opaque and translucent structures don walls and shelves, casting shadows and reflecting light across the room.

Welcome to the Morean Glass Studio – one of four community-oriented art spaces under the Morean banner. Daily, visitors trickle in from the Morean Arts Center and Chihuly Collection across the street to be dazzled by glass art. Ornaments, wavy paperweights, bowls and nameless forms blur the lines between utility and art.

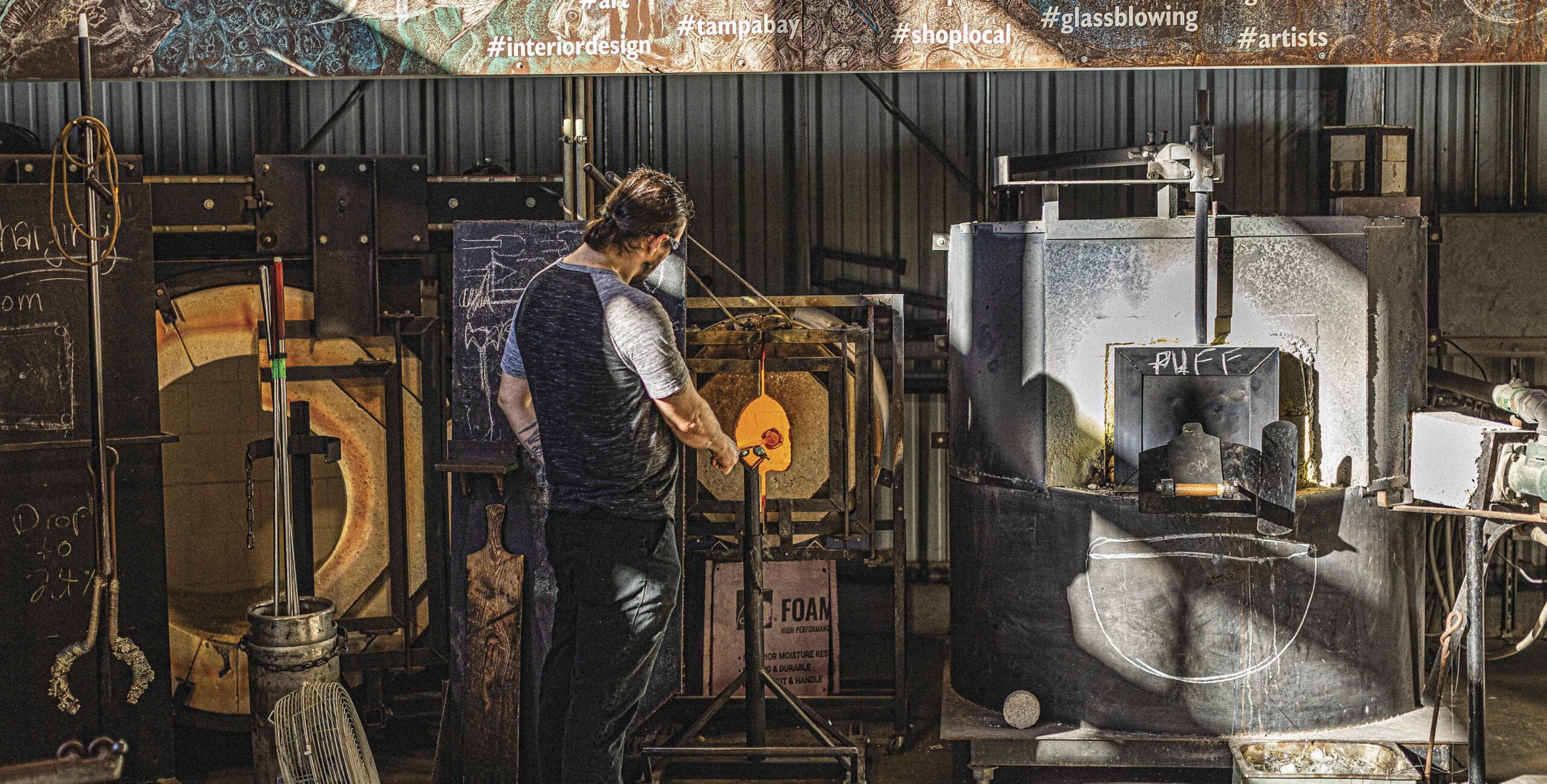

In back rooms and outside in the hot shop, glass is heated, blown and shaped. A few times a day, visitors sit wide-eyed as they watch master artists dip rods into the fire, pull out a hot, glowing, molten form – and alchemize it into art before their eyes.

Helming the ship is studio manager Tim Soluna. His work is permeated by two themes, an interest in the circus arts and more predominantly – the Venetian style of glasswork, mainly of the 1400s to 1700s. Soluna reproduces Venetian patterning and technique through the labor-intensive practice of caneworking—resulting in rich patterns, crisscrossing striped lines and stunning geometric shapes.

“The material called to me,” Soluna describes. “The way the glass would heat up and glow and move and solidify right in front of your eyes — it just seemed magical.”

In St. Petersburg, the name Morean is a beacon among the arts community. The organization made headlines when, in 2010, it purchased a vast collection of works from American glass art pioneer Dale Chihuly for a permanent collection.

Passionate about arts education and making art accessible, Chihuly had one condition for the sale — the creation of a glass art studio that would engage the community in education. Thus, the Morean Glass Studio was born.

For the 10 artists working within, the medium of choice requires not only skill, but chemistry. Glass workers start with volumes of silica (sand) mixed with measured proportions of soda, ash and lime. Placed into a crucible furnace, the mixture gradually melts and morphs into 400 pounds of molten glass. The studio goes through a batch about every five days and Soluna says about 50 pounds of each ends up spilled or broken.

The glass is heated to 2,100 degrees before 4-foot steel pipes are dipped into a pool of glass lava and a golden orb is pulled out. Artists move their breath through the hollow tube, creating a bubble in the glass on the other end. The glass is shaped with hand tools into the artist’s desired form.

The pieces are cooled over 12 to 14 hours. But then, is it solid? It depends on whom you ask.

“Different physicists have different answers,” Soluna notes in a brief physics lesson. “Some call glass an amorphous solid and some call it a super viscous liquid. A solid material, in physics, is considered to have a rigid crystalline structure with four, six or eight connection points. A liquid has a chain structure with only two connection points. Glass stays in that chain structure, but when it cools, the molecules get packed so tightly that they barely move at all.”

Theoretically, if you can wrap your head around it—a time-traveling glass artist would have to go 10,000 to 50,000 years into the future to find his work slumped or melted.

The theory remains untested, as the oldest human-made glass known is only 4,000 to 5,000 years old. But if historians are correct, human fascination with glass art has been occurring for much longer.

“Glassmaking predates written history,” Soluna says. “We’ve been making glass since at least 6,000 to 8,000 years ago and from what I understand, blowing glass for 2,000 years.”

Soluna is not the only glass worker fascinated by the history and legacy of glass. Benjamin Ugol is the newest and youngest gaffer at Morean. After spending two years in Murano, Italy, learning from Grand Maestro Davide Salvadore, he brought his fascination with the Venetian style to Morean and now leads demos for the public alongside fellow glass workers, such as master glassblower Harry Boux.

“We’re lucky here; there are five studios in about a 2-mile radius,” Ugol says. “At Morean, I’m happy. The people are great and I’m able to bring my dog to work.”

Two years may seem long, but a typical glass apprenticeship can run five to seven years, and in Italy it’s not uncommon to apprentice for 12 to 15 years.

Harry Boux has been playing with fire since he was old enough to pick up a blowpipe. The son of Chuck Boux, founder of Sigma Glass Studio (Pinellas County’s first glassblowing studio), the younger Boux also demos at Morean.

“To see people’s reaction and share my take on the work with the public, it’s what I love about this place and the main reason I’m here,” he describes. “Glass is going through its renaissance, advancing more now than it has for the past 2,000 years. It’s amazing to be a part of.”

Inside the shop, the artists’ unique influences and styles are apparent as the eye travels from one display to the next. Anjali Singh is the only female glassblower leading demos and classes at Morean, forging her path in an industry dominated by males.

“I’m proud of being a female glassblower,” she says. “I bring that into my work. I like dainty and feminine themes, curves and small intricate designs. I like that someone can look at my work and say, ‘I think a woman created that.’”

In our modern era, instant gratification is at the tip of our fingers and luxuries abound. Against the grain are the artists at Morean dedicating their lives to an art that is challenging and demanding. At Morean, one sees the glass art renaissance clearly – driven by those unafraid to play with fire and shatter some glass in pursuit of something magical.

Check out Tampa-based glassblower, Susan Gott.