Written By Derek Herscovici

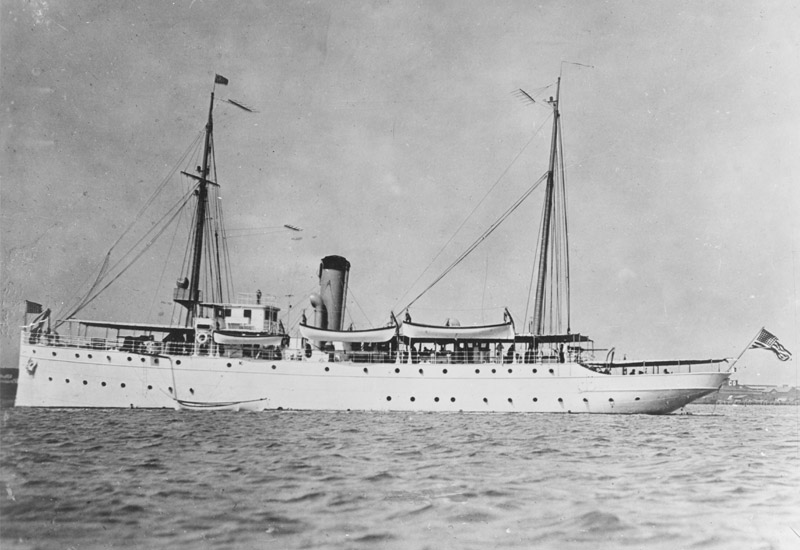

September 26, 1918 – The Tampa, a United States Coast Guard Cutter ship, just finished leading a convoy of ships from the coast of Gibraltar to the Irish Sea and prepares to make its return journey in the Bristol Channel.

The Tampa and its crew – 115 officers and men, many of whom were Tampa natives – would be lost, however, sunk by a German submarine torpedo as evening set on the Atlantic.

It’s a story seldom told, but thanks to the joined efforts of a passionate and selfless group of Tampa activists the Tampa will finally have a memorial on the shores of the Bay it once called home.

“Nobody’s heard of them because they’ve been forgotten, but they’re not going to be forgotten again,” said Nancy Turner, author of “The History of Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla, 1904-1979.” Turner has provided research and historical documents for a textbook on the Tampa written by local author Robin Gonzalez and funded by the Saunders and Duckwall foundations.

On February 3, 2018 – 100 years after the Tampa’s sinking – the Tampa Bay History Center and other regional partners will dedicate a memorial along the Riverwalk to the ship and its crew lost at sea.

Oddly enough, this story doesn’t begin with the Tampa, but with the Miami.

Launched out of Virginia on February 10, 1912, the Miami was the latest in a long line of “cutter ships” built more for speed than cargo and was used to catch smugglers and pirates during the 19th century.

The Miami’s first job was iceberg scouting in the north Atlantic Ocean, a task made more important with the recent sinking of the Titanic. When it wasn’t mapping ice flows, the Miami was a beloved dockside fixture in Key West and Tampa.

In 1915, the Revenue Cutter Service was joined with the US Life Saving Service to form the United States Coast Guard; less than a year later, the Miami was rechristened the USCGC Tampa and redeployed along the Eastern Seaboard.

Falling under US Navy jurisdiction at the start of the nation’s entry into World War I, the Tampa underwent heavy rearmament to prepare for combat. It retained the speed of a cutter ship with greater firepower, perfect for protecting convoys of cargo ships sailing along the western coast of Europe.

It was good at its job, too. In 11 months, the Tampa escorted 18 convoys totaling 350 ships and lost only two, averaging over 3,500 nautical miles a month. Though it fired its guns a few times, its only real encounter with a German U-Boat proved to be fatal.

Using German military records, scholars traced a log entry from that day stating “submarine UB-91 spotted the Tampa entering the Bristol Channel, submerged and fired a torpedo into the ship’s stern around 8:15 p.m.” The strike was not fatal, but as water filled the ship, its stockpile of depth charges reached detonation depth and exploded. There were no survivors.

The death of all 131 aboard remains the largest single loss of life in US Navy history. There are memorials to the crew in Arlington National Cemetery, at Brookwood American Cemetery in England and even on the coast of Gibraltar, but not in Tampa.

Turner, Gonzalez and the other dedicated Tampa activists plan on changing the ending of this story for good.

“Kids will go home and they’ll tell their parents and grandparents and their whole families,” Turner said. “The story of the Tampa won’t be lost to history anymore.”

“Nobody’s heard of them because they’ve been forgotten, but they’re not going to be forgotten again.”

View the local memorial at:

The American Legion “U.S.S. Tampa” Post 5

3810 W. Kennedy Blvd.

Tampa, FL 33609

post5tampa.org/history