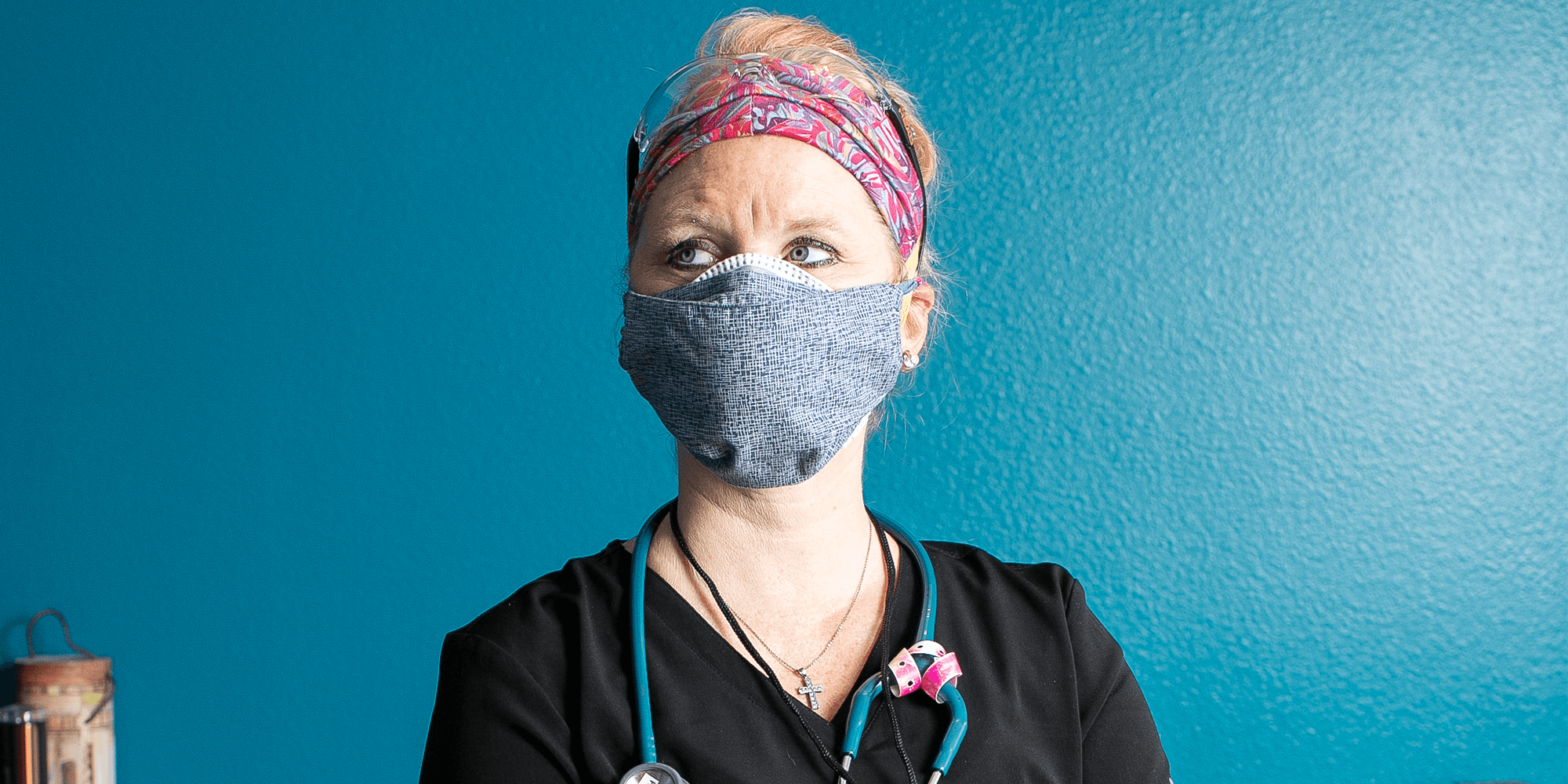

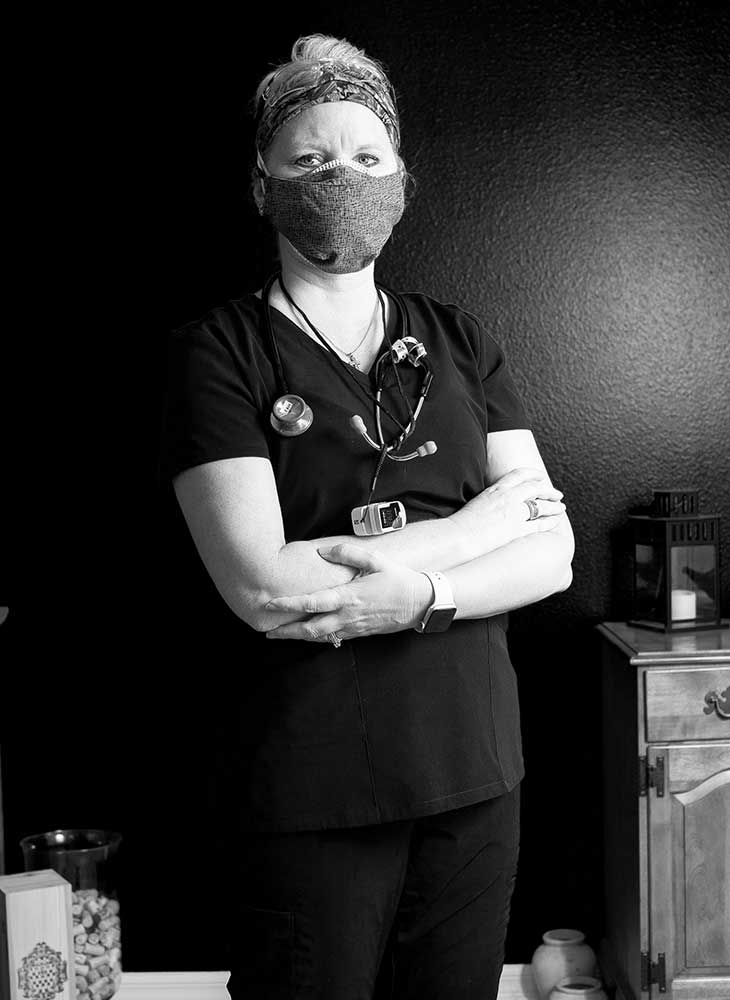

Leah Churchill has had a hard time sleeping through the night recently. She’s haunted by nightmares and memories of the horrors she saw during her eight weeks volunteering in a COVID ward at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York.

“It was basically a war zone,” she says.

Today, the Moffitt Cancer Center nurse awoke around 2:30 a.m. She checked her phone and found she wasn’t the only one struggling to shut off her brain.

“My [fellow nurse] who was there with me texted me and said, I just can’t sleep, are you up? I was like, actually, yeah I am,” Churchill recalls. “We’re just trying to get through it.”

The first time Churchill was awoken in the middle of the night, it was early April, and God was sending her a message: Go to New York. Those people need you.

“So, 3:30 in the morning, I was on the computer filling out an application,” Churchill says. She had begun receiving calls and emails from recruiters by the start of business hours, and 10 days later, she had taken a leave of absence from Moffitt and was on the road to New York.

Before coming to Moffitt three years ago, Churchill had spent the previous two decades of her career working in the emergency room and critical care. She thinks it’s because of that experience that she was assigned to what was called the “black unit” when she arrived at the Brooklyn hospital. Churchill describes this makeshift ward as the destination for COVID patients who were too sick for even the ICU; for the vast majority of these patients, it was where they went to die.

“By the time they got to me, you couldn’t do anything for them because they were so severely ill,” Churchill says. “It was, keep them alive as long as you can.”

Because the virus is so new, the nurses and doctors were constantly trying different treatments and techniques — from UV light to proning, a maneuver to turn patients on their stomach — to see what worked. Almost nothing did. Churchill estimates anywhere between three and six black unit patients would pass away each night.

“It felt like Groundhog Day every single day,” she recalls. “You would walk into work, and [think], hopefully we only have two people die tonight and not three. Hopefully we only have one person die and not two. Maybe we won’t have anyone die and I can keep them alive tonight. It’s like you were walking into defeat every time you went into work.”

Despite the heavy emotional toll each day took, Churchill and her fellow nurses saw their mission clearly. “I think my purpose was just to be there for the patients,” she says. “I’d pray over them every night. We’d video chat with their families so they could see them.”

In the black unit, nurses were randomly assigned to any patient that didn’t already have a nurse attending to them, so Churchill met many patients and families during her eight weeks at the hospital. Families weren’t allowed in the hospital, so the nurses would set up video chats for patients and their loved ones, getting to know them in the process. One family she got to know particularly well was that of her only black unit patient to survive COVID and be released from the hospital. Churchill says the odds were stacked against this patient, who was overweight and had both diabetes and asthma, but she stuck it out.

“She should not have made it. But by golly, that sucker, she made it,” Churchill says with a laugh.

There was not a whole lot of hope to be found in that hospital, she says. Churchill returned to Florida in mid-June, right around the time this state’s caseload began to spike. She’s concerned that some people are not taking the proper precautions to prevent the virus from spreading and fears a possible surge like the one she witnessed in New York.

“This is a real thing, and you have to protect yourself and the others around you,” Churchill says. “You can still do things, but just keep protected.”

She understands the hesitation and even resistance to wearing masks, but considering she and the rest of her nursing team consistently tested negative for both the virus and its antibodies despite being as close as one can be to COVID patients, Churchill says she is living proof that they are effective in stopping the spread.

“I just wish people would take it seriously. It’s for real,” she says. “We don’t want to be another New York, that’s for sure.”