Like many cities, Tampa’s history is long enough to fill the pages of books; attempting to tell the whole thing in one issue of a magazine would be futile. Instead, TAMPA Magazine is sharing glimpses into Tampa’s past as told by three of its children, each of whom has lived in the city since birth or early childhood. In their stories on the following pages, these individuals illuminate how a patchwork of backgrounds and identities have fused to become a city — and what it means to be a true Tampeño.

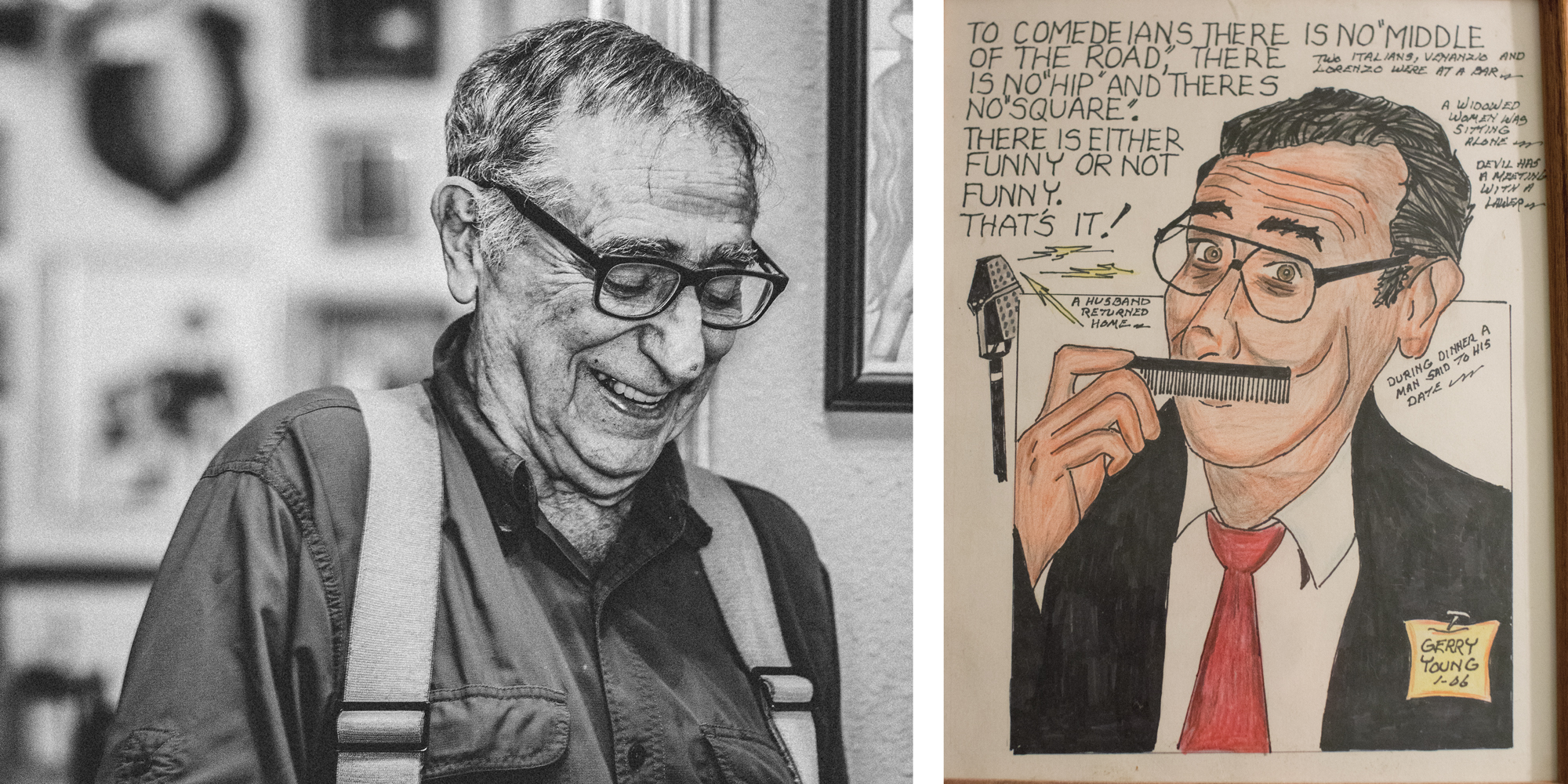

Jack Espinosa

The essence of Ybor City native Jack Espinosa’s roaming journey through life is perhaps best summed up in this anecdote: one day, he was Plant High School’s night janitor. Literally the next day, he was its newest social studies teacher. “I put the broom up, put a tie on and went in the next morning to teach United States history,” he says.

He was perfectly qualified, he explains. The janitor job had helped put him through college at the University of Tampa, and he had recently graduated with a degree in U.S. history. From the minute the newly dubbed Mr. Espinosa had his students burn the inane textbook outlines that had previously been their only assignments, the students were his. He went on to teach for a time at both Jefferson High School, his alma mater, and King High School. “I’m not bragging. I was one hell of a teacher,” Espinosa says.

The 88-year-old Espinosa’s reputation as a “sacafiesta,” which loosely translates to “life of the party,” began as a child of Spanish and Cuban-Irish parents growing up in Ybor. He got his start in school plays at V.M. Ybor Elementary and George Washington Junior High, eventually finding his knack for comedy and developing his signature pantomime routine at the variety shows held each month at the Cuban Club, Centro Español and other mutual aid societies.

“If you were an aspirant for music or comedy or acting, you had theatres [in Ybor City] with spotlights, with footlights. Nobody had that anywhere coming up,” Espinosa says. “It’s a hell of an audience. You clear your throat, and they’re laughing. There’s nothing like it.”

His biggest laughs came about 330 miles away in Havana, where he unexpectedly became an over-night comedy sensation in the early 1950s. While in the city on a goodwill trip, Espinosa had the chance to audition for Cabaret Regalias, Cuba’s top TV variety program. Espinosa soon had the show’s producer in stitches with a humorous, lip-synced rendition of the Spike Jones song “Cocktails for Two”; he secured a regular time slot on the show for the next seven years, where he performed on the same bill as the likes of singer Nat King Cole and actress Lana Turner. He took the 90-minute flight to Havana superstardom every Wednesday, returning to Tampa the same day or the following morning to relative anonymity.

“In Cuba, I get off the plane, and they attacked me for autographs,” Espinosa recalls. “When I get off the plane here, maybe a tumbleweed would go by.”

It was one of many careers Espinosa embarked on over his lifetime. Since he began working as a bread delivery boy at 8 years old (in Ybor City, “everybody worked,” he says), Espinosa has been a standup comedian, teacher, busboy at Ruben’s restaurant on Tampa Street, employee of the city’s welfare department, assistant Hillsborough County administrator, and spokesperson for the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office. It’s enough to fill Espinosa’s two memoirs (titled Cuban Bread Crumbs and Sacafiesta).

“The [connecting] line is that all of that happened to me because I lived in this town,” Espinosa says. “The doors were hard because of the prejudice, but overcoming it… I’m always pushing. I don’t stop.”

Espinosa says the Spanish, Cuban and Italian people he grew up with faced discrimination based on their ethnicities. Though Espinosa had a bachelor’s degree, Plant High principal Shorty Wilson was concerned about the reception a teacher with a Spanish last name would receive at the all-white high school, despite his desperate need to fill the position. Kids in Ybor City had been raised to aspire to nothing more than a job as a waiter or a mailman, says Espinosa — something with a uniform and a badge.

But, as the city and county have exploded with growth, Espinosa explains, people like him have done the work to create change. Today, his son, Jack Jr., is a judge on the county circuit court.

“You cannot imagine what a trip that is. You’d have told my grandfather that he was going to have a great-grandson that would be a judge…” Espinosa says, trailing off in thought.

Tampa is what it is because of those Spanish, Cuban and Italian immigrants who — instead of self-segregating into ethnic ghettoes like they did in New York City — lived, worked and toiled side-by-side, Espinosa explains. And when their kids met on the schoolyard, they worked out their differences the Ybor way.

“Public school took care of us. We beat the hell out of each other for the first two or three years in elementary school,” Espinosa says with a chuckle, “But after a while we were fine.”

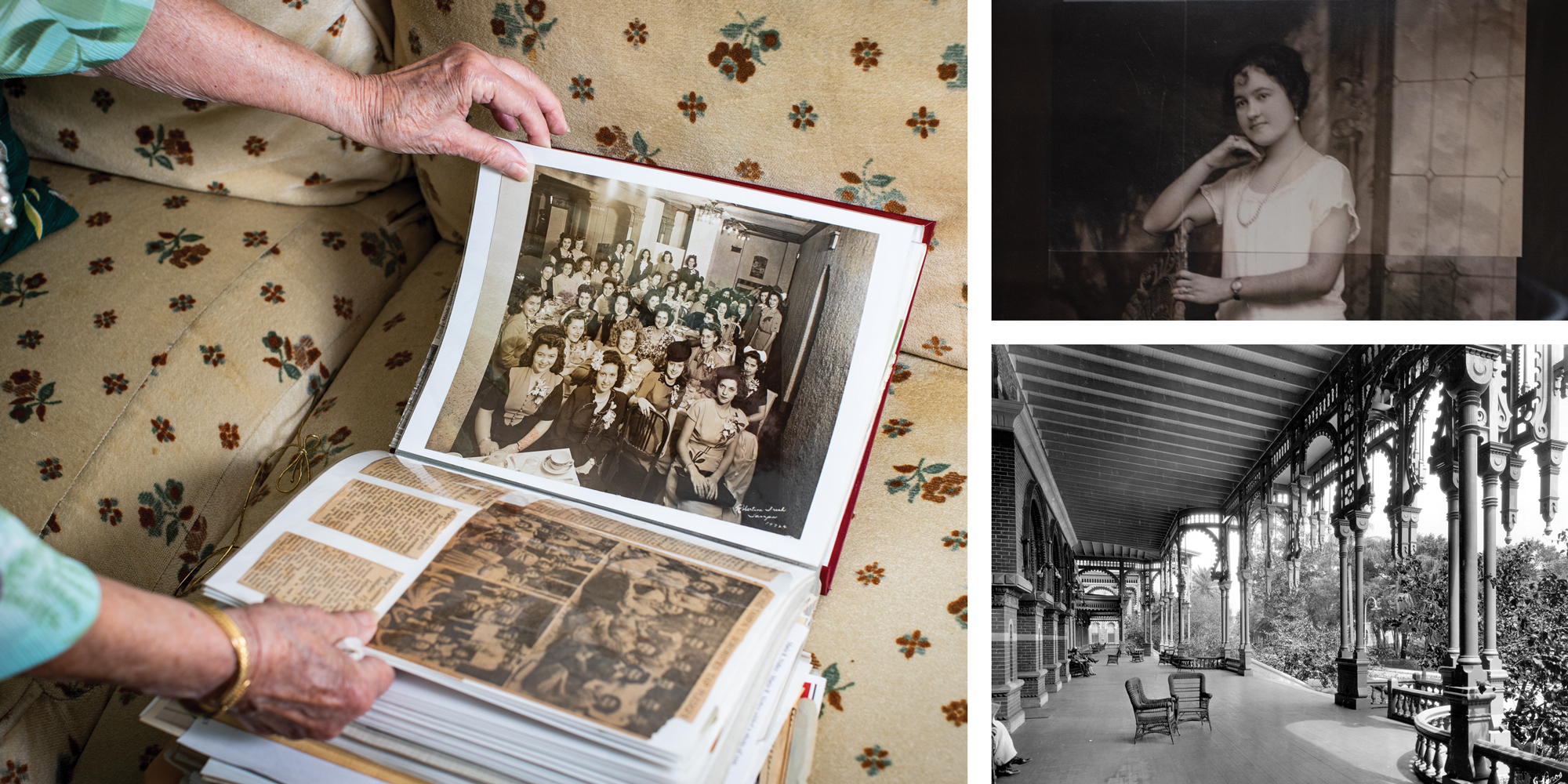

Mary Cagnina

Most of what Mary Cagnina (then LiCalsi) knew of Tampa before mov-ing here at 12 years old came from her grandmother, who visited the city with her husband from their homeland of Sicily — and it didn’t leave a particularly positive impression.

“My grandmother didn’t like Tampa because she said there were alligators coming out from under the house,” Cagnina, 91, says. “A lot of people didn’t know there were alligators in Ybor City.”

With the alligator situation cleared up, Cagnina’s family moved from Manhattan in 1939. When their train arrived in Tampa, the family was greeted by friends and loved ones of Cagnina’s mother, who had lived in Tampa until she married her husband at age 17 and relocated to his home in New York. Cagnina’s father, a successful upholsterer, had a two-story building erected on Florida Avenue, with one floor for his shop and one floor for the family to live. Cagnina’s living room is still full of couches, chairs and curtains her father made.

Perhaps the most important consequence of the family’s move to Tampa was a young Mary getting the opportunity to pursue higher education, becoming the first person in her family to graduate from college.

“My father said, someday you’re going to go to the University of Tampa,” Cagnina recalls. “Always in his mind, he thought, if I have children, I want them to have the best education they can get.”

Cagnina enrolled at Tampa U, as it was called then, in 1944 after graduating from Jefferson High School. With the country at war, the university had only 150 students — the vast majority of them women and many of them from the Tampa area. Cagnina studied education with the intention of becoming a teacher and eagerly participated in as many extracurriculars as she could, from the chorus to Spanish club to the sorority Alpha Gamma. She took two streetcars to campus from her home in Tampa Heights.

“It was a wonderful experience for me,” she says. “I was very grateful the university was there. If it wasn’t there, I don’t think that my father could have afforded to send me to college in Gainesville or Tallahassee.”

Cagnina’s lifelong passion was teaching, which she began at Tampa Bay Boulevard Elementary School after graduating from college in 1948. She says she grew to love her students’ parents as much as the kids themselves.

“They were just wonderful people,” she says. “They just loved me to death. In those days, not too many mothers had gone to college, so they would look up to their teachers.”

She was recognized by the Hillsborough County School District for her commitment to the profession when she retired in 1979. “It takes a lot of dedication. When you’re teaching, you have to love those children because you want them to succeed,” she says. “I wasn’t just teaching reading, writing and arithmetic. I wanted these children to be better citizens.”

Cagnina’s trailblazing streak continued even to marriage; she married her husband of 45 years, Joe, when she was 27 — a decade older than her mother was when she wed. The newlyweds bought two lots in South Tampa’s Palma Ceia neighborhood, where Cagnina still lives in one of the two homes they built on the property. Today, she sees old friends at the Sons of Italy club occasionally and goes out to eat (something she didn’t do growing up until a college sorority banquet at Las Novedades) with other former educators. None of her four children and five grandchildren live close enough to visit often, something Cagnina says she misses about the way Tampa used to be, when it seemed like Hillsborough Avenue was the city limit.

“People lived in small communities. Like in Ybor City, they all gathered together — the cousins, the mothers, the fathers, the grandparents,” she recalls. “They all lived close by, whether it was in Ybor City or West Tampa. Nowadays you don’t see that. Everybody goes their own way.”

Still, Cagnina reflects on her life more frequently these days, particularly her father’s choice to uproot the family from Manhattan. Unquestionably, it was the right one.

“I’m so glad he made that decision to come down here,” she says. “I like Tampa. I really do. I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.”

Alice Prida

Alice Prida swears she has never met a bad per-son in her 92 years. From the time she was growing up on Columbus Drive in Ybor City, the small-town community was a supportive and generous one.

“The people in Ybor City were very good to each other. They knew everybody had hard living,” she says. “I knew people who, if you needed money, you would go to and say, I need money.” Prida slides her hand across the table as if passing along a sum of cash. “They’d say, pay me whenever you want.”

Prida, then Martinez, was raised in one of three houses built by her paternal great-grandfather after he arrived from Spain via Cuba, with her aunt, uncle and cousins living just upstairs (“Families kept together no matter what, even if you all had differences,” Prida notes). Life was simple, and Prida walked the handful of blocks to V.M. Ybor Elementary School and later George Washington Junior High with her mother watching from the sidewalk. By the time she got to Jefferson High School — at the time located in Tampa Heights — she was expected to add to the family income brought in by her parents, who worked in Ybor cigar factories. Prida would hop on the streetcar every day after school to get to her job at a downtown loan office; at 5 p.m., she’d make the journey home to Ybor.

Downtown, she learned, was not Ybor City. Prida had to push through the business community’s prejudice against anyone who wasn’t white. “They would not hire Latin girls to work because they thought that they weren’t smart enough,” Prida recalls. “But you know what? When they started hiring those girls, they wanted those Latin girls instead of the others because they worked harder. They would stay after work if they had to. They would come early if they had to. So then everybody wanted a Latin girl to work downtown.”

Her life changed forever in the summer of 1943, when she began receiving letters from a recently graduated Jefferson classmate who had been drafted to fight on the war’s European front. Alice had never spoken to Luciano Prida — handsome and a star athlete, he had been popular with the girls — but he wrote to her with a request: wait for me, and marry me when I return. Puzzled, Alice said no to his proposal but agreed to continue corresponding. The two continued writing letters during the war until Luciano was shot in the foot and the messages stopped coming. Alice didn’t hear from him again until, a few months later, he and a friend appeared at the streetcar stop next to her home. They exchanged hellos; she graduated from high school in 1945, and by 1946, they were married.

After a short stint at the University of Tampa, Luciano finished his accounting degree at the University of Florida in 1950 (the only time Prida lived outside of Tampa her whole life) and opened his own firm in 1957. Prida helped her husband run the business while also raising their five children; today, the couple’s oldest son, Luciano Prida Jr., is the president of Prida Guida & Perez, P.A. on Franklin Street downtown.

One constant throughout Prida’s life has been her love of dance. As a child she would go to the monthly dances held by the Centro Español, Centro Asturiano and the Cuban Club — mutual aid societies created by Ybor’s Spanish, Cuban and Italian immigrants to provide social and medical support to their communities. Later in life, Prida danced all over Tampa with a group through the city’s recreation department, and she has the ribbons and medals to prove it.

“Any group that wanted us to dance, we’d come dance,” she says, beaming with pride. “Let me tell you, I enjoyed every bit of it.”

Despite watching the town she grew up in change beyond her recognition (“Ybor City doesn’t exist [as it did] anymore,” she says), Alice Prida is still certain of one thing.

“I’ve never had dealings with any bad human being as of yet.”