Everyone loves a good sandwich. Since many who live in the Tampa Bay area are not from here, they likely brought their preferences with them, be they cheesesteaks from Philadelphia, dipped roast beef from Chicago or pastrami on rye from New York City.

The Bay area has its own sandwich traditions. The Cuban sandwich is king, but new research may indicate that it isn’t exactly ours – at least not completely. (A book recently published by the University Press of Florida on the history of the Cuban sandwich theorizes that Tampa should share credit for the Cuban’s creation with Key West and even New York City.) However, one sandwich does indeed have all of its roots firmly planted in West Central Florida and that is the grouper sandwich.

Grouper hasn’t always been considered a high-end fish for eating. An early reference in the Tampa Tribune from the early 1900s related that fishermen at Port Tampa were using small grouper as bait for redfish. The transition from baitfish to table fare did not take long and soon local fishing fleets were targeting a wide variety of grouper species. Among the most prized was the goliath grouper due to its size.

For the next several decades, grouper remained on dinner menus, though not as much as snapper and pompano. Early references to fish sandwiches on lunch menus were unfortunately too vague to know what fish was actually being served.

After World War II, beach culture began to take hold in Florida. Beachfront restaurants, as well as landlocked seafood places, began to highlight the bounty that came from local waters. Old favorites like snapper and pompano, along with grouper, were advertised alongside flounder, shrimp and crabs as either specials or daily fare.

The late Buster Agliano, a member of one of Tampa’s early, prominent fishing families, claimed to be the first to introduce the grouper sandwich to local restaurant menus. The story goes that grouper was not a very desirable fish in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, so Agliano and others promoted a new way to serve it – fried and served on a bun with tartar sauce.

However, in looking at prices for grouper during that time, both for the consumer at fish markets and grocery stores and on restaurant menus and advertisements, it appears that grouper held its own compared to most other fish with the exception of snapper and pompano. In fact, the Tampa Tribune ran a brief story in October 1969 stating that the Florida Department of Agriculture had developed a test to determine the types of fish and meat being served, pointing out that “the next time the sign says snapper fingers, you can rest assured it is snapper fingers and not grouper.”

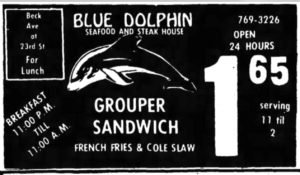

Unfortunately, without any other independent evidence, we probably will never know the actual origin of the sandwich. We do know, though, that the first time it appeared in a restaurant advertisement was for the Blue Dolphin Seafood and Steakhouse in Panama City in 1974. Still, stories abound about a proto-grouper sandwich in Bay area restaurants earlier that decade.

By the mid-1970s, restaurants all over West Central Florida featured the sandwich on their menus. Always fried, the meal was affordable, but not necessarily a bargain. By the end of the decade, two Pinellas County restaurants emerged as the leaders in the grouper sandwich game. The Hurricane Lounge on Pass-a-Grille has been selling its famous grouper sandwich since 1977. On the north end of the Pinellas peninsula, Frenchy’s opened its first location in Clearwater in 1980. Owned and operated by Mike “Frenchy” Preston, the restaurant started offering the sandwich soon after opening. Across the bay, it found its way onto the menu of the iconic Colonnade Restaurant on Bayshore Boulevard by the mid-1980s.

Regardless of when, where and why it came to be, by the 1980s the grouper sandwich had become one of the most popular menu items in the state. It was during this time that a new preparation method for the grouper sandwich hit the scene. Based on the Cajun- and creole-inspired cooking (and cookbooks) of New Orleans chef Paul Prudhomme and in particular the popularization of blackened redfish, Florida cooks began to add blackened grouper as an option in their sandwiches to enhance the flavor of the mild fish. The ever-increasing popularity led to two different events, one environmental and the other more scandalous, that shook the world of the grouper sandwich.

The increased demand for grouper, both as an entrée and in sandwich form, put incredible pressure on the fishing industry and, even more alarming to environmentalists, on the goliath grouper population. The huge fish were being harvested out of existence, so the state stepped in and banned commercial and recreational harvesting of the goliath grouper in the early 1990s.

This led, either directly or indirectly, to the great grouper sandwich scandal of the early 2000s. Numerous consumer groups and media outlets began to investigate restaurants and fish suppliers due to rumors that the fish being served as grouper was an imposter (an ironic twist given the alleged substitution of grouper for snapper back in the late 1960s). A variety of less expensive, lesser quality fish were allegedly being substituted for the real thing. DNA tests and legal testimony soon followed and the results were upsetting, if not shocking – indeed, many diners were chowing down on tilefish and tilapia, not authentic grouper.

As could be expected, prices spiked for “guaranteed grouper” in the scandal’s aftermath. Now the phrase “market rate” is much more common than an actual price on restaurant menus.

New players continue to enter the world of the grouper sandwich and South Tampa’s Big Ray’s Fish Camp is among the most celebrated. Diners can still visit some of the originators of the tasty sandwich as well, including both the Hurricane and Frenchy’s in Pinellas County.

So while there is certainly a place for a Philly cheesesteak, a beef on weck or a lobster roll, native Floridians and new residents alike can be proud of our local favorite – the grouper sandwich.

Rodney Kite-Powell is a Tampa-born author, the official historian of Hillsborough County and the director of the Touchton Map Library at the Tampa Bay History Center, where he has worked since 1995.

Sandwich fan? Check out our 2022 Sandwich Hunt Winners.