Have you noticed the small concrete structure on Bayshore Boulevard near the Jose Gasparilla II pirate ship? Since 1995 it has been the site of “Fish On Bayshore,” public art by Lorraine Genovar and Wayne Fernandez featuring five colorful mixed-media fish. But originally it displayed and weighed the real thing — not just any fish, but the Atlantic tarpon, aka the silver king.

Recreational tarpon fishing on Florida’s west coast dates to the late 1800s. Sportsmen from around the country took a train to Charlotte Harbor to fish Boca Grande. By the early 1920s, tarpon fishing tournaments were held in Fort Myers, Venice and Sarasota. Tampa fishermen considered starting one of their own in 1928, but pressing economic problems likely sank the proposition before it could get started.

Finally the Tampa Junior Chamber of Commerce and the Tampa Daily Times united to co-sponsor the first annual Tampa Tarpon Tournament from June 1 to Aug. 19, 1934. It included all Bay-area waters up to a line between Pinellas and Piney points (roughly where today’s Sunshine Skyway Bridge is). Participation was open to any man, woman or child. Guides were available for hire for a flat fee of $7.50 per party of three per tide (the equivalent of around $160 today).

In addition to trophies, tournament organizers acquired a variety of gender stereotyped prizes for entrants. The man who caught the largest tarpon won a new rod and reel, while the woman was gifted a hospitality tray by Tampa Electric. The most fish caught netted the male a rod and reel, while the female got a pair of slacks from Maas Brothers.

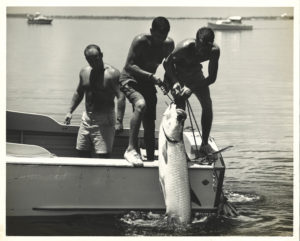

The first awards ceremony took place at the Hillsborough Hotel in Downtown Tampa. Earl R. Oberlin’s 147-pound tarpon, caught near Davis Islands, took top prize. Marian Pitts picked up the top two women’s categories and took home a stand mixer, bowl and pants, along with a trophy for the most tarpon caught by anyone.

The tournament ran annually for the next seven years. It had different sponsors and plenty of prizes, but the boundaries and participants remained largely unchanged. World War II and particularly the fear of German U-Boats in the Gulf put the tournament on ice. Once the war ended, the idea of an annual tarpon tournament reemerged. In 1946, the Tampa Tribune revived its tournament, which covered Florida’s entire Gulf Coast. It survived one more year and in 1948 came the rebirth of the local Tampa Tarpon Tournament.

The revamped tournament had many of the same leaders from the pre-war version, particularly Red Hall and Ralph Elliott. Joining them as founders of the new tournament were J. C. Hughey, Ray Wireck, Claude Hanes Jr., plus Dick and Jack Whiteside. The Whitesides owned Tampa’s iconic Colonnade Restaurant on Bayshore.

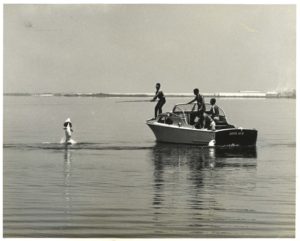

The tournament grew every year and by the 1960s, it was among the largest in the state. Prizes included cash, fishing gear and for the top angler, a new car. Fishermen from around the U.S. flocked to the area during summer for a chance at landing one of Tampa Bay’s famed silver kings.

The tournament came to an end in 1974. Tribune outdoor writer Herb Allen blamed the burdens of promoting the event, which he dubbed cumbersome and said “fell on the shoulders of a few volunteers who finally just got tired.” Also part of the problem, years of harvesting the inedible fish took its toll on overall numbers of adult fish available to replenish the species.

Water pollution was another major factor. Reminiscing 11 years after the last event, tournament veteran A. J. Grimaldi said, “At one time Tampa Bay was the hottest tarpon fishing spot in the world,” and the annual event was a major boost to the area, hosting over 5,000 anglers. But he noted that decades of raw sewage, plus unregulated dredging projects led to killing off the Bay’s seagrass, which triggered a chain reaction up the food aquatic chain.

Hillsborough and Tampa bays’ health vastly improved over the past several decades. Raw sewage is no longer pumped directly into the water and responsible dredging policies helped boost seagrass. Conservation efforts regarding tarpon’s catch and release also helped the fish populations recover. Tarpon have returned to the bays, though not enough to prompt another tournament.

Yet tournament memories live on, from the art on Bayshore to the name of the Yankees Single-A minor league team, the Tampa Tarpons. That too is a revival of history that stretches back to the days of the Cincinnati Reds spring training and Al Lopez Field. But that is a story for another day.

Rodney Kite-Powell is a Tampa-born author, the official historian of Hillsborough County and the director of the Touchton Map Library at the Tampa Bay History Center, where he has worked since 1995