Tampa’s most prized tradition was sparked 118 years ago and continues to be shrouded in some mystery. Gasparilla, the city’s most popular annual event, centered around a pirate-themed parade, resulted from a conversation seeking to spice up an existing parade.

It all started in the newsroom of the now-defunct Tampa Morning Tribune, where Society Page Editor Louise Francis Dodge sought to energize the city’s annual May Festival. George W. Hardee, a New Orleans native who worked in Tampa for the U.S. Customs Service, suggested that they add a Mardi Gras-style element and incorporate a mythical pirate, Jose Gaspar. Hardee spoke with several young, local businessmen and organized a new social club, Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla (YMKG).

On April 23, 1904, the Tribune ran a story on the return of an ancient band of pirates. On the eve of the May Festival, the krewe’s pirate ship, the Octopus, was sighted about 40 miles down the coast. A word of warning accompanied it: “Anyone sitting up to see the arrival will be summarily shot by order of the Pirate-Chief.”

The pirates, about 50 YMKG members, made their appearance two days later, but rather than pillage and plunder, they joined the May Festival parade in costumes from New Orleans, many on horseback. That day, May 5, 1904, Tampa witnessed the first invasion of Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla. The parade was a hit, as was the krewe’s coronation ball held two days later at the Tampa Bay Hotel (now the Henry B. Plant Museum).

Dodge and Hardee get credit for creating Gasparilla, and Hardee and the krewe more so for crafting Gaspar’s backstory (including giving him the first name Jose and a death date of 1821). But the idea of a pirate named Gasparilla (or some variant) goes way back. Despite its long history, there is no definitive origin of the name. It is believed that it first appeared on maps of Florida in the 1770s. The Bernard Romans map of 1774 may be the earliest appearance (Boca Gasparilla, or Gasparilla Pass), but some sources allude to an unidentified map printed in 1772 that also identifies the place name. The best hypothesis is that the name comes from a Spanish priest, who lived on what is now Gasparilla Island, and went by the name Gaspar.

The leap from priest to pirate happened about 120 years later, likely to draw tourists to southwest Florida. The early story had as many contradictions as it did creators. Juan Gomez was among the ones most often identified as a creator or perpetuator of Gaspar’s story. His own story – that he lived to the age of 122 – is far-fetched enough to believe. He claimed to be a member of Gaspar’s crew, appearing in stories of hidden treasure. Though it is much more likely that he was exercising his imagination, his stories became part of the Gasparilla legend.

Another man with a wild imagination also contributed to the legend. Tampa mystic and conman Luis de Ricardo was arrested and put on trial in 1901 for swindling three local ship carpenters out of a few hundred dollars so they could talk to spirits who would reveal the buried treasure of a Spanish pirate named Gasparilla. As it turned out, there were no spirits and there was likely no treasure, but there was a conviction. Ricardo ended up in jail for fraud.

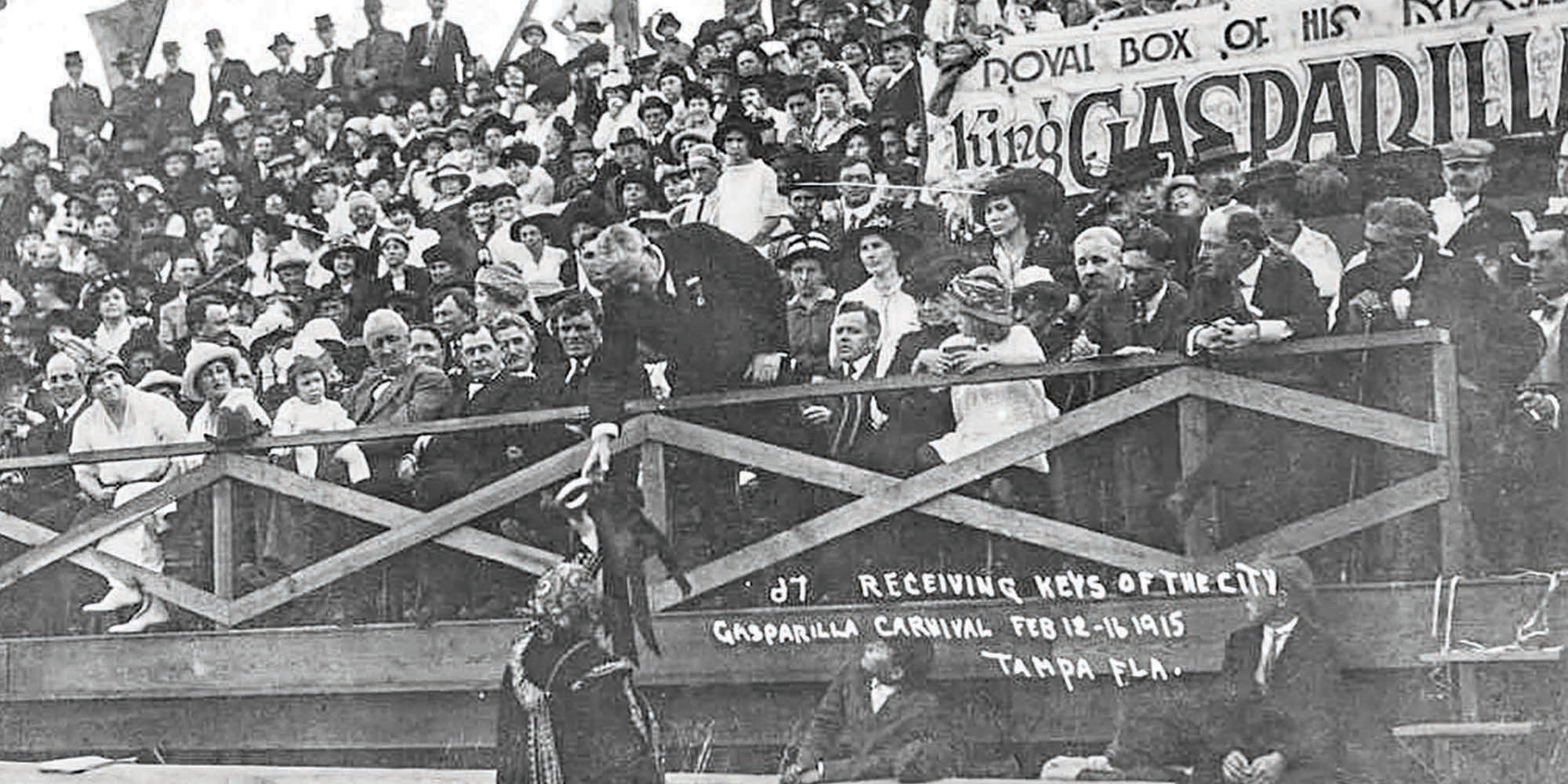

Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla returned to invade Tampa in 1905 and 1906, with the fledgling parade coinciding with the new South Florida Fair in November. The parade vanished until February 1910, highlighting Tampa’s Panama Canal Celebration. The following year, 1911, marked the first time Ye Mystic Krewe “invaded” the city by ship, with cannons blazing to clear the way. The scope of the parade has vastly increased over the years, with elaborate coronation parties, more krewes and additional parades, but the original idea remains.

The Gasparilla invasion has returned almost every year since 1910. There have been a few interruptions, though. The two longest disruptions were the result of global conflict, namely World War I and World War II. Another pause, in 1991, came when another street carnival, Bamboleo, briefly replaced the annual pirate celebration. The most recent break came in 2021 due to COVID-19.

The present-day parade has a national corporate sponsor and is as much a marketing tool for the Bay area as it is a celebration of a mythical pirate. However, children still jockey for the best position to catch beads and coins, and crowds throng to the waterfront to catch a glimpse of the Jose Gasparilla II and the accompanying flotilla. The city and its citizens continue to turn the city over to a band of pirates, even if only for a day.