The creation of community gardens—and the planting of home gardens—took on a special significance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Facing supply chain problems, lockdowns and a reduced workforce people created their own spaces or came together in small groups to plant and grow fruit and vegetables.

A similar initiative took place across the nation during both world wars in the form of Victory Gardens. Often dubbed War Gardens during World War I, the name changed to Victory Gardens at the end to allow large U.S. farms to supply food to war-ravaged European countries. Local farms and home gardens helped make up the gap created by shipping food to Europe. One example in Tarpon Springs showed a wide variety of vegetables, including lettuce, onions, turnips, carrots, collards, celery, beets, parsley, mustard, Swiss chard and radishes.

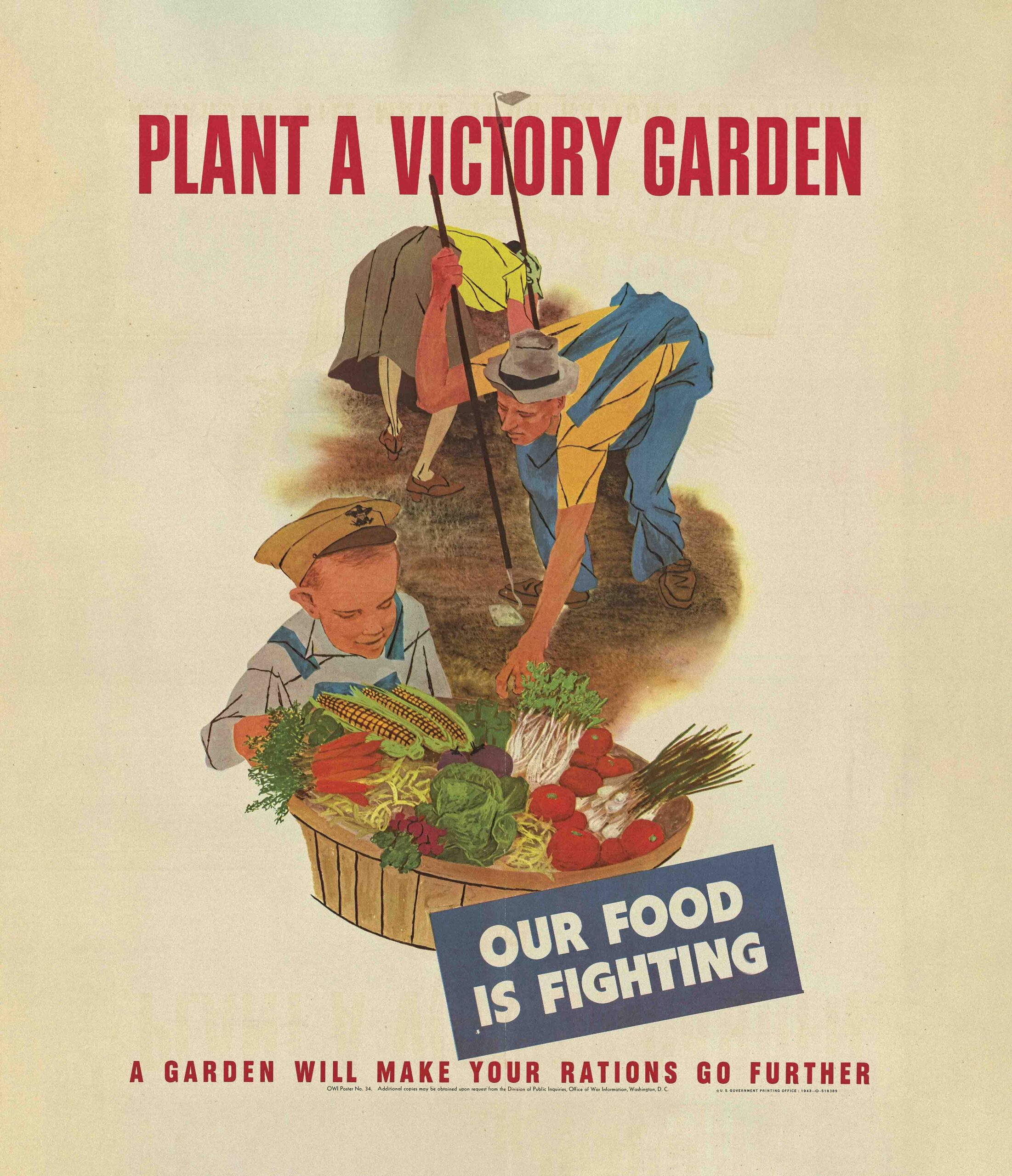

Fast forward to 1942. The U.S. had entered World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. War planning necessitated rationing food and encouraging a variety of creative solutions on the home front. Scrap metal drives, sewing circles (for everything from parachutes to bandages) and home gardens, first dubbed Defense Gardens, were all part of the war effort.

By 1943 rationing was a part of everyday life. That shared experience of shortages, as well as the shared efforts at tackling those shortages, gave people a sense of contributing to the war effort. Among the things near and dear to the hearts of Tampa’s Latin community was café con leche, which was sweetened with copious amounts of sugar. Rationing of coffee and sugar put a dent in that daily routine.

Interviewed in the late 1990s by historian Gary Mormino, Willie Garcia remembered how his father dealt with those shortages: “My daddy, Manuel Garcia, had a café next door to Cuesta-Rey called the Atlanta Restaurant… He brought coffee to Cuesta-Rey’s 400 to 500 workers three times a day. He was allotted a certain amount of sugar each month. By the end of the month, we would run low on sugar. My father would then tell the cigar makers, ‘The coffee is not going to be as sweet.’ So the workers brought in their ration coupons so my dad could buy enough sugar to sweeten the café.”

While people weren’t regularly planting sugarcane in their backyards, a wide variety of fruits and vegetables were planted to help fill the gap left by food shortages. Newspapers like the Tampa Tribune, Tampa Daily Times and the St. Petersburg Times ran advertisements and stories relating information about the types of crops that could be grown, as well as lessons on how to preserve what you grew for long-term storage. Topics such as canning, pickling and drying—tasks that would have been familiar to earlier generations—were gaining renewed significance.

Those lessons were important because many who lived in the immediate city suburbs were a bit removed from a more rural existence. For others, in the words of Mormino, who were “only a generation removed from Georgia farms and European villages, gardening remained part of their urban lifestyle.” One Sulphur Springs resident recalled that his father had grown up on a farm, “so we always had a garden; during the war we raised chickens both for sale and for the eggs.”

In Ybor City, Sicilian immigrant Paolo (Paul) Pizzo, father of future Ybor City booster and historian Tony Pizzo, planted a Defense Garden in the vacant lot next to his family’s home in February 1942. As quoted in the Tampa Tribune at the time, Pizzo’s “peas, carrots, collard greens and eggplant [were] doing nicely through [his] diligent work.”

Others who lived in the Tampa Bay area during the war remembered raising rabbits as a substitute for beef and pork, both of which were strictly rationed. Though chickens were more prevalent and were not subject to rationing, one Ybor City resident fondly reminisced about his mother’s yellow rice and rabbit, and southern fried rabbit.

In addition to Victory Gardens and rabbit hutches, Bay area residents took advantage of the bounty of the Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Those who had the time and talent could catch their dinner from boats, seawalls and shorelines. Rapidly rising prices awaited those who caught their fish at a market instead of from the water. Pompano, at 90 cents per pound in 1943, cost more than steak. Gulf shrimp were a bit less, at 50 cents per pound. Mullet, a traditionally inexpensive species, went for 23 cents per pound, but this was a 16-cent-per-pound increase from just a few years before (for reference, $1 in 1943 equals about $17 today).

The end of the war also brought the end of rationing, though not immediately for all items that were controlled in that way. By the late 1940s, though, prosperity was returning and new ways of food preparation and consumption began to separate people even more from the traditional garden. Canned fruits and vegetables became the norm, and pre-packaged meals soon followed. A return to fresh foods grew in popularity in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but it took the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent shortages and access limitations to bring some people back to their roots and back to the home garden.

Rodney Kite-Powell is a Tampa-born author, the official historian of Hillsborough County and the director of the Touchton Map Library at the Tampa Bay History Center, where he has worked since 1995.

Check out the History & Evolution of Tampa’s Hospitals & Health Care.