South Tampa’s Ballast Point has been a destination for picnickers and fishermen for over 120 years. Geographically speaking, the area has long been a local landmark, possibly since the earliest days of Florida’s indigenous people. It is often asked, how — and when — did Ballast Point get its name? The answer dates back to the early 1820s and the arrival of the first U.S. citizens.

Ever since the first deep-draft ships entered what is now Hillsborough Bay, the southern end of the Interbay Peninsula has signaled the beginning of the shallow water. Most sea-going ships could not enter the bay and make it up to Tampa and Fort Brooke without dropping their ballast overboard. By the same token, those same ships would need to add ballast to their holds when leaving the bay for the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Ballast is extra weight that would be placed down in the ship’s hold for stability in deep, and potentially rough, seas. This could be something as simple as sea water held in casks or tanks. While that certainly was the case for some ships coming to and leaving Tampa, others held a more interesting type of ballast — heavy rocks that contained colorful crystals known as geodes.

Those rocks may have been the feature identified as “black rocks” on Thomas Jefferys’ chart of Tampa and Hillsborough Bay in 1777. Twenty years earlier, Spanish naval officer Franciso Celi created a chart of the bay and named that same point Punta de Montalvo, in honor of Lorenzo Montalvo, one of Celi’s Spanish Navy superiors.

Capt. James McKay established a small wharf at Ballast Point in the 1850s that handled a variety of imports and exports, especially cattle, off and on through the mid to late 19th century. This rudimentary port would be replaced by facilities at Port Tampa (across the peninsula) beginning in the 1880s and later by the Port of Tampa.

Ballast Point’s future did not lie in its cargo, but rather in its leisure. Emelia Chapin, who came to Tampa around 1890, brought a park complete with pavilion, gazebo and pier to Ballast Point. Chapin, who along with her husband owned Consumers Electric Light and Street Railway Company, named the new park after her favorite author, Jules Verne.

Verne used Tampa (called Tampa-Town in the tale) as the setting for “From the Earth to the Moon,” a science-fiction novel about space travel. Though Verne, a Frenchman, never visited Florida (and did not completely understand the state’s geography) his placement of a launch site for a rocket to the moon proved interestingly close — Cape Canaveral is almost directly across the state.

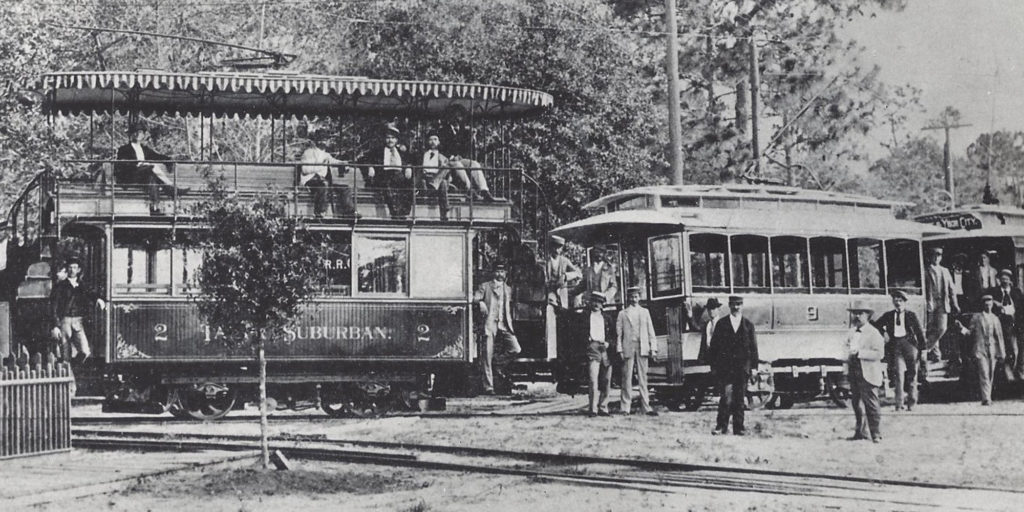

Consumers Electric extended streetcar service to Ballast Point in 1893, connecting the relaxing destination within an easy ride and 5-cent fare from almost anywhere in the city. When Tampa Electric took over operation of streetcar service in 1899, there were 21.5 miles of track in and around Tampa.

Within 15 years, there were 47 miles of track. The fare, however, never increased, and access to Ballast Point and Jules Verne Park rapidly grew.

The Pavilion at Ballast Point had a Japanese theme, architecturally, with interestingly crafted rafter tails and roof details. The once-proud centerpiece of the area is long gone now. It was damaged during the devastating 1921 Hurricane but repaired and used as a dance hall and dining spot. A 70-foot-tall Ferris wheel was built next to it in 1922, but by 1924 it was an eyesore and the city had it dismantled. Shortly after, a fire destroyed the old pavilion. The matching gazebo, originally built by the Chapins and restored by the City of Tampa, still stands. That gazebo is now surrounded by new features installed by the city’s parks and recreation department.

Another longtime feature of Ballast Point, the pier, remains popular. Day and night, it is filled with people — from anglers to exercisers, bird watchers to stargazers. Though styles have changed through the years, there are incredible similarities between old photographs of the pier and scenes of today.

While the original streetcar line stopped carrying passengers to Ballast Point over 70 years ago, there remains a tangible reminder of that service. Just off to the side of Interbay Boulevard, on the western edge of the park, sits the covered streetcar waiting area, the scene of countless departures and arrivals to one of Tampa’s oldest summertime destinations. There is a strong possibility, though still unconfirmed, that the structure also served the Black community.

That idea comes from a photograph taken at Ballast Point of passengers getting on and off of the streetcar – white people on the right side of the photo and Black people on the left. In the background on the left sits an open-frame wood structure that strongly resembles the building on Interbay Boulevard. Further research is needed to either confirm or discount this theory. What is not in dispute is the importance of Ballast Point to both Tampa’s history and the recreation needs of the city’s residents.